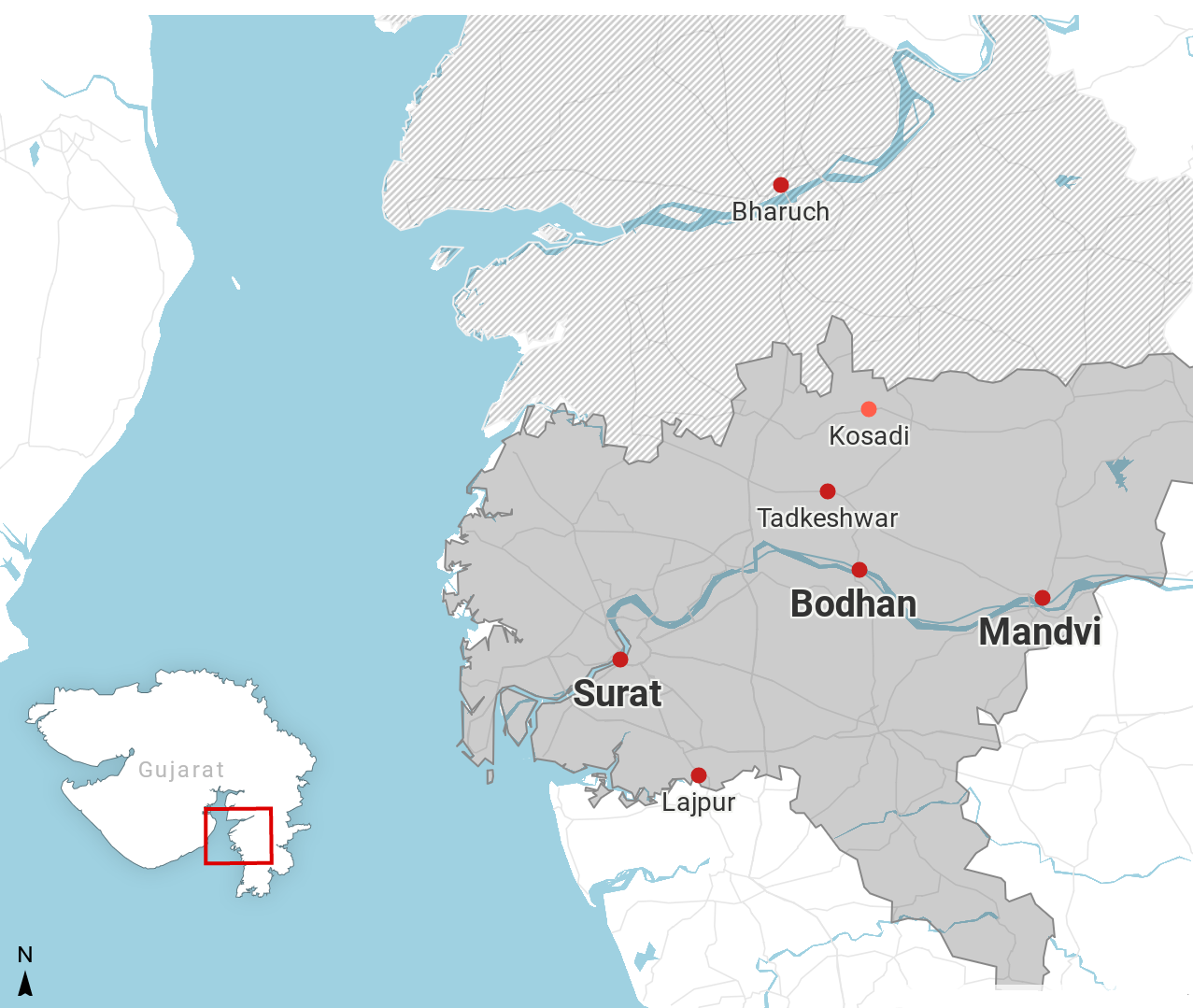

It was at daybreak on Friday 19 January 1810 (corresponding to 13 Dhu ’l-Hijjah 1224 AH) when the people of the village of Bodhan, a quiet, unassuming and unfortified village situated on the banks of the Tapi River in the Surat district of Gujarat, came to realise a sudden calamity was about to befall them. [1]A note on transliteration. Colonial-era spellings are invariably inconsistent. The name ‘‘Abdur Rahman’ may appear as ‘Ubdal Rehman’ and also ‘Ubdal Rahman.’ Likewise, the word ‘fakir’ is transliterated as ‘faquir’ and also ‘fakir.’ I have retained colonial spellings in quotes to ensure the language remains as close to the original sources as possible and at places included a more acceptable transliteration in brackets.

The previous night, Nathan Crow, the East India Company’s Chief at Surat, had dispatched cavalry to Bodhan. Made up entirely of British soldiers, the cavalry was from the 56th Regiment. Following them not so far behind was an infantry regiment that was yet to arrive.

These were auspicious days. On the preceding Tuesday, Bodhan’s Muslims most likely celebrated Eid al-Adha which normally involved sacrificing animals in the footsteps of the Prophet Ibrahim (peace be upon him). Little would they have known that this year it would not just be animals that would be slaughtered in their village. As the sun rose, the East India Company cavalry appeared on the other side of the Tapi. Armed and ready to attack, the sight of these troops dressed in crimson red must have been chilling.

Anti-colonialism

Inspired by stories of Sufis who rebelled against mighty colonial powers across the Muslim world, it was in my teens in the 90s that I once asked my late father whether he knew of any such rebellions in our native Gujarat. He recalled hearing that something happened in Bodhan but was unsure of the details. What he said centred on a Sufi shaykh and his murids who, armed with bamboo sticks, staged a rebellion against the British. My dad knew the village well as he was born and raised in the nearby village of Tadkeshwar, situated short of 10 miles northwest of Bodhan.

I found his response fascinating but then the image of Gujarati villagers armed with bamboo sticks reminded me of the BBC sitcom Dad’s Army. Was it true, did this happen or is it one of those urban legends that at times takes a life of its own and is repeated so often that people turn fiction into fact? Bodhan and its supposed rebellion, however, moved to the back of my mind. I was sceptical but not dismissive. Oral accounts of history come with their own problems, but there could very well be an element of truth in them and it was only decades later that I was able to get more information of what possibly happened in Bodhan in 1810.

East India Company in Gujarat

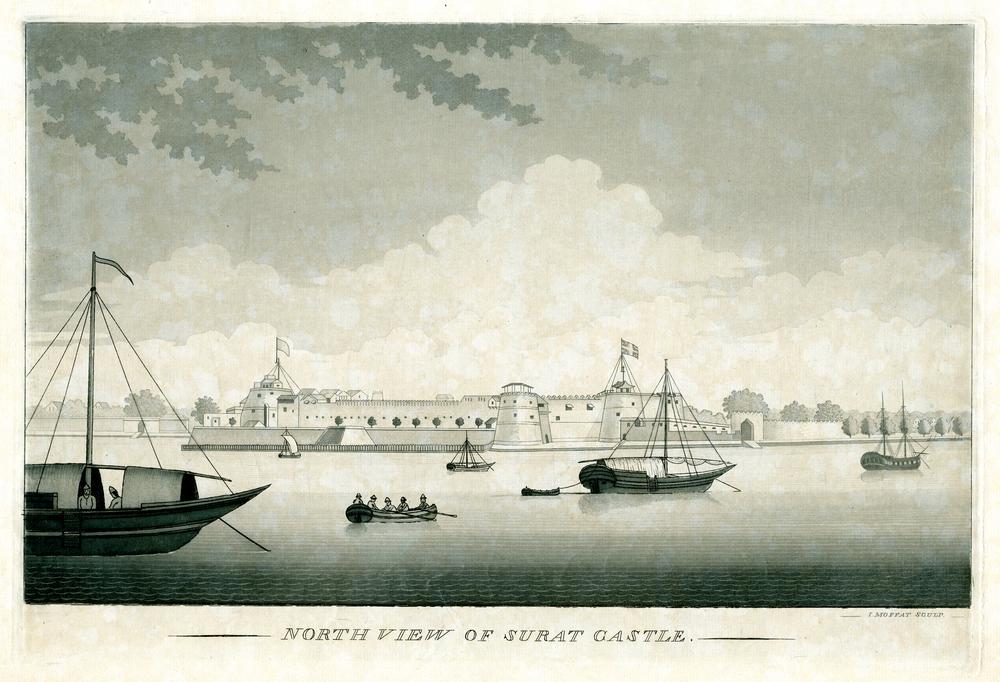

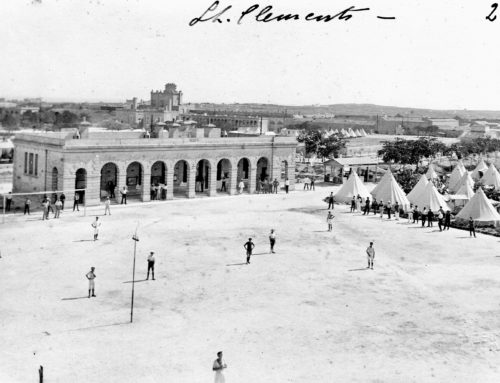

Having initially arrived in India after being granted a Royal Charter from Queen Elizabeth I in 1600 for a monopoly on trade, the East India Company established its first factory in Surat in 1612. Over time, the Company’s interests turned to the lucrative business of territory, and as the Mughal Empire declined following the death of Aurangzeb in 1707 it began annexing vast tracts of the Subcontinent. Following a siege and naval attack on India’s greatest port, Surat, in 1759, the Company took control of its admiralty and 16th century castle that had been built by the Gujarat Sultanate to defend the city from frequent Portuguese attacks. The city’s civil and criminal administration, meanwhile, remained with the local Muslim nawab. By 1800, however, the Company was able to take control of the city’s administration and in this way it became the dominant power in Surat and also vast chunks of Gujarat (Hamilton, 1828).

This was a period when East India Company hegemony in Western India and certainly India was not totally complete. The Company was the major power having pushed aside its French and Dutch competitors, yet it was still vying with some Indian contenders for supremacy in the face of a weakening and crumbling Mughal Empire. It was only following the Treaty of Bassein between the Company and the Maratha Peshwa of Pune in 1802 that the British were able to establish paramount power in Western India. The treaty meant that the Princely State of Mandvi came under British influence. Situated around 15 miles upriver from Bodhan on the banks of the Tapi and some 38 miles from Surat, Mandvi had, until that point, paid tribute to the Gaikwad Maharajas of Baroda. As a vassal state of the British it was subject to an annual tribute of 65,000 rupees.

Not densely populated and “thinly peopled by predatory Bheels,” the state of Mandvi (not to be confused with the port town of Mandvi in the Kutch area of Gujarat) was mainly covered with jungle and had originally been founded by a Bhil chieftain “whose successors gradually acquired sufficient power to raise themselves to the rank of petty sovereigns…” [2]The Bhils are an ethnic group found in western India and considered the indigenous people of the states of several states, including Gujarat. The Bhils rebelled on several occasions during the colonial period and were designated as a criminal tribe by the British Indian Empire under the Criminal Tribes Act 1871. In modern India, the Bhil are classified as a Scheduled Tribe. It was some twenty-five miles long and fifteen miles wide and, according to the Bombay Gazetteer, had a population of 4,430 people in the 1870s. Having come under Company influence, Mandvi’s raja evaded payment for seven years and the British were on the point of reducing the tribute to 25,000 rupees when trouble flared up in Bodhan (Aitchison, 1864). [3]The State of Mandvi functioned until 1839 when the direct line of succession became extinct and the state was thereafter treated as an escheat and annexed to the British dominions.

Happenings in Bodhan

Having wrested possession of Surat Castle in 1759, the East India Company used the fort as its headquarters. It was here that Nathan Crow first learned on 10 January 1810 of a “revolution having taken place at Mandvie, in favour of Musulman…” This was some nine days before Company troops first arrived at Bodhan (Briggs, 1849). As a civil servant of the East India Company, Crow was no stranger to intrigue. Prior to taking up his post in Surat, he was one of the main Company players behind a covert political mission to Sindh under the pretext of trade where he reopened the Company’s factory in Tatta in 1799. This subsequently enabled the Company’s subjugation of Sindh. Successful in this endeavour, Crow was appointed Surat’s judge and magistrate in 1800 (The Asiatic Annual Register 1801, 1802).

What Crow had come to learn centred on Bodhan whose people he described as “chiefly cultivating Bohoras of the Sunni sect” who had come under the sway of a Sufi dervish called Miya ‘Abdur Rahman (Campbell J. M., 1879). [4]The Sunni Bohras (also known as Vohras) are several traditionally endogamous Muslim communities found in Gujarat. Though some ethnographers (Misra, 1964) claim they are primarily agrarian communities that converted to Islam, it would, seem that they are of mixture of ancestry – some may have certainly converted while others are descendants of foreign Muslim groups (Arabs and Persians) who over the centuries settled in Gujarat. Misra identifies several regional sections of the Sunni Bohras … Continue reading Crow’s account of what took place is meticulously recorded in a detailed letter to the then Governor of Bombay Jonathan Duncan that was subsequently published in the Asiatic Annual Register (Briggs, 1849). In his letter Crow writes that it was on the evening of Wednesday 10 January that Sevanund, the brother of Mandvi’s vizier Sookanun, came to Surat with news that his brother was “killed by the Borahs, at the instigation of a wild Fakir (or Sufi), named Ubdal Rehman (‘Abdur Rahman)” and that the raja, so he thought, had been “put to flight… to another small position of his” called Pardi, near Valsad or Bulsar. It later transpired that this was not the case, the raja was held captive in Mandvi for several days and only managed to escape a few days later. [5]Pardi, also called Kila Pardi, is home to a fort (kila or qil‘ah) built by the Maratha warrior-king Shivaji (d.1680).

According to British sources, including the Bombay Gazetteer, Miya ‘Abdur Rahman had proclaimed himself the awaited Imam Mahdi, “captured the fort of Mandvi and made prisoners of the chief and his minister. The chief effected his escape from confinement [much later], but the minister was killed.” Having taken Mandvi, Miya ‘Abdur Rahman returned to Bodhan while a group of his followers, who had been joined by around 275 Arabs (most likely Hadhramis from the Hadhramaut region of the Yemen), remained in Mandvi. [6]It is most likely that the Arabs referred to here were Hadhrami mercenaries from Yemen who were known to have taken up military roles under various Indian rulers during this period. Though Arabs entered Gujarat as traders before the Muslim period, there are no traces of the early Arabs (Misra, 1964). Misra writes that the Arabs found when he carried out his research came mainly in the 18th century to enlist into the forces of Indian princes. In his letter, Crow also writes that news of insurrection spread like wildfire across Surat.

Bodhan’s dervish

There is little known about Miya ‘Abdur Rahman, which Sufi silsilah he belonged to, whether he had studied and if so under whom. There is no mention of him in hagiographies of scholars and saints resident in Gujarat during the 18th and 19th century such as the Haqiqat-i-Surat. According to one recent writer, Deepak Bardoli, he was from north India (Bardoli, 2011). [7]Deepak Bardoli is the penname (takhallus) of Musaji Yusufji Hafiz of Bardoli. His book, Sunni Vohra Samaj Tarikh keh Aina, includes a short write up of what took place in Bodhan in 1810. Written in Gujarati, I am grateful to Mawlana Ismail Kawthar Kawthari (a resident of the village of Kosadi in Surat) who sent me an Urdu translation of the relevant sections. All that we know is that he resided in Bodhan and had a following among the cultivating Sunni “Gamudia” (or village) Bohras (also spelt Vohras) of the area. [8]According to late 19th century British sources, Bodhan was a place of Hindu pilgrimage and had a population then of 3,305 (Campbell J. M., 1879).

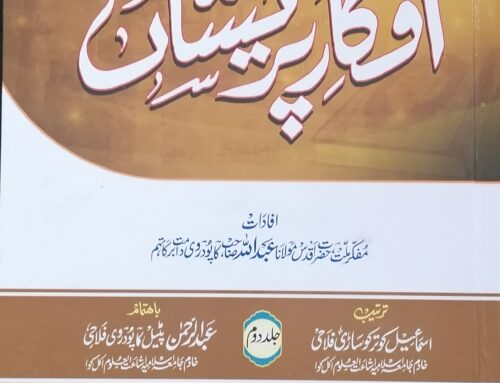

He is, however, mentioned briefly in the biography of Sufi Sulayman Diwan Lajpuri (d.1924), a famous Gujarati dervish from the village of Lajpur. This biography is included in a book called Bagh-i-‘Arif which is a collection of Sufi Sulayman’s writings on Sufism and Islamic jurisprudence compiled and published by his son several years after his demise in 1937. [9]Sufi Sulayman Diwan was a Sufi of the Naqshbandi and Shadhli orders from the village of Lajpur, Gujarat. He received khilafah from Shaykh Nizamuddin Mujaddidi (d.1866) of Bajaur (situated in what is today the Malakand Division of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in Pakistan). Shaykh Nizamuddin lived and died in Tadkeshwar, Surat, and was also the shaykh of Haji Musaji Mehtar (d. circa 1891), the famous Naqshbandi Sufi of Tadkeshwar. During a trip to the Hijaz, Sufi Sahib received khilafah in … Continue reading The biography discusses Sufi Sulayman’s age and the claim that he lived for over 120 years. It is in this section that his son recalls how his father mentioned the Bodhan incident, which he remembered from his childhood and which is then used to estimate his age. Sufi Sulayman relates that “two men from Lajpur—who in their own words would say, ‘Why are we sitting, let’s go there’—went there themselves and were martyred. I saw them and this incident took place in the Hindu year of 1866…”

Sufi Sulayman continues,

“In the village of Bodhan lived a dervish. His murids would always say to him, ‘Hudur, awaken the faith (din jagaw), awaken the faith.’ On one occasion, all of a sudden, the dervish, in a state of spiritual rapture, said din (faith) and all of the murids with bamboo sticks in hand came out in combat and began to force non-Muslims to become Muslims. Whoever would not bring faith, they would kill them. This incident became so famous that ordinary Muslims from great distances and from nearby areas began coming in huge groups and participated in this combat until they also got hold of the raja of that place and forced him to become Muslim. He, apparently, under duress brought faith. However, finding an opportunity he secretly escaped …”

Readers should be cautious in how this text is approached. There are several issues with it that leads one to question its veracity and whether it is an authentic account of occurrences. The author wrote the book some 120 years after the incident in Bodhan and was not alive at the time let alone a witness to it. The narrator, meanwhile, was alive but not present and only a child at the time. Compiled so many years after the Bodhan incident, it may be the case that facts may have become fuzzy. [10]Bagh-i-‘Arif is attributed to Sufi Sulayman and was originally published in 1937 by Khilafat Press, Bombay. Compiled by his son, it also includes a short but interesting biography of Sufi Sulayman in which the 1810 incident in Bodhan is mentioned. A new edition of this book was published by Majlis-e-Dawatul Haq, Leicester, in 2007. Even if it were to be assumed that the account is accurate, it should be borne in mind that forcing non-Muslims to accept Islam is un-Islamic and contrary to the Qur’anic injunction: “There is no compulsion in Faith.” (2:256)

Anyhow, according to Bagh-i-‘Arif, Miya ‘Abdur Rahman was prone to lose himself in spiritual rapture (jadhb), something that in effect meant he was a majdhub (someone who is spiritually infatuated or besotted in the love of the Divine that temporal awareness pales into insignificance). This is also something that Bardoli also mentions that on one occasion Miya ‘Abdur Rahman said “I am the messiah (masih), Spirit of Allah (Ruhullah), I am the Mahdi of the final time,” that he was able to see the treasures in the earth and that he has been commanded by the Prophet (may Allah bless him and grant him peace) to end disbelief, guide people and wage war against those who do not follow him.

A letter to Crow

Crow continues with the story. He writes that it was on Saturday 13 January that he received a letter from Miya ‘Abdur Rahman asking him to pay the person carrying the letter 300 rupees or to quit Surat.

“To Mr. Crow Sahib, with Meen Sahib’s (Miya Sahib) compliments from boodhan (Bodhan). My man is come to you; pay him three hundred rupees, (300), and if you will not do it, you may get into another place. The man is about to proceed to Baroda, therefore deliver him the aforesaid sum, and return him… The person’s name is Sooliman, who comes to you: pay him the said sum, and dispatch him.”

Though the letter was dated 11 January it only reached Crow two days later on 13 January. The messenger, Sulayman, remained at Bodhan and instead sent the letter with a “coolie” who Crow detained. Clearly, the delay in the letter reaching its intended recipient coupled with the messenger asking a labourer to deliver it in his stead is indicative of Sulayman’s apprehension in personally conveying the message. Meanwhile, the situation in Surat was tense with Company officials closely monitoring developments. According to Crow “a great number of people had quitted the city to join the fanatic, and the Mahometans generally began to assume a very threatening air.”

Eid al-Adha was to be celebrated on Tuesday 16 January and on the day before (Monday 15 January) East India officials in Surat arrested a Sufi called Sayyid Pir Shah along with three accomplices who had arrived in the city from Bodhan. Shah, a native of the Punjab and aged around 40, had a bizarre message from Miya ‘Abdur Rahman for Sayyid Muhammad Hada, a Muslim scholar who was in the Company’s service employed as a molwi in Surat’s High Court. [11]Sayyid Muhammad Hada and his brother Sayyid Ahmad Hada are mentioned in the Haqiqat al-Surat, a Persian biographical dictionary of the 18th and 19th century by Shaykh Bakhshu Miya (d.1849) and his son Shaykh Shaykhu Miya (d.1911). The version I have before me is an Urdu translation by Professor Mahbub Hussayn ‘Abbasi published by the Gujarat Urdu Academy (published in 2005). According to Haqiqat al-Surat, Sayyid Muhammad Hada was from the Qadri family of sayyids, whose saintly ancestors were … Continue reading When questioned, Shah revealed that he had visited Miya ‘Abdur Rahman around four days before and stayed in Bodhan for two nights. When he took leave for Surat to travel to Makkah, he was asked to carry a message for Sayyid Hada asking him to tell Crow that Miya ‘Abdur Rahman is the Ahmad mentioned in the New Testament and that “he must conform to his orders, otherwise get away.”

The next day (Tuesday 16 January) was Eid al-Adha. Crow writes that he attended the Eid ceremony in Surat which was “marked by the absence of the general number of Mahometans parading on the occasion, and an evident fear in the Hindoos, who had been very generally threatened by the circumcised tribe.” It would seem that huge numbers of people had left Surat and the nearby town of Rander, possibly out of fear that trouble was brewing or even join those in Bodhan. Crow writes that those in Bodhan were crying out the word din, din and that “there was every cause to suppose, from the expression of Ubdul Rehman, that he was intent upon bringing about a revolution in the city.”

A second letter

Crow continues that the following day (Wednesday 17 January) he received a further letter from Miya ‘Abdur Rahman that had been sent with two Bohras from Bodhan. If the letter can be considered authentic then its contents were more bizarre than the previous messages. According to Crow, Miya ‘Abdur Rahman claimed to be the awaited Imam Mahdi and asked Crow to accept Islam, retire or fight. The contents of the letter are (if assumed to be authentic) clearly contrary to orthodox Islam and an indication that he had lost himself in jazb. In Crow’s version of the letter Miya ‘Abdur Rahman claims to have arrived from the fourth skies with four bodies: that of himself and the Prophets Adam, ‘Isa and Muhammad (may Allah bless them and grant them peace). He also wrote that he had no gun or musket except for a stick and a handkerchief.

“To all counsellors, and the Hakim of Surat; be it known that the Emaumul Deen (Imam al-Din – the Imam of the Faith), of the end of the world, or Emaum Mehdee (the Imam Mahdi), has now published himself, and the name of this Durveish is Ahmud; and that is the Hindovie, they call him Rajah Nukluk. Be it further known to you that if the Esslaum (the Mahometan faith) is accepted, it is better, otherwise empty the town, or, on the contrary, you may prepare for battle. This fakir is now come down from the fourth Sky, with four bodies; combining Adam (on whom be peace,) Essah the son of Marium, (Jesus the son of Mary,) and Ahmud (on whom be peace,) and they have all four come upon one place; they have no guns nor muskets with them, but a stick and a handkerchief are with me,—be yourself prepared.”

As can be understood from the letter (if it is assumed to be really from him), Miya ‘Abdur Rahman and his murids were unarmed and also clearly not in a sound state of mind. While the coming of Imam Mahdi in the final days has been foretold by the Prophet Muhammad (may Allah bless him and grant him peace) and accepted by scholars as a point of belief since the time of the Companions and Followers, Miya ‘Abdur Rahman was not the awaited Mahdi, nor could he possibly have embodied the above mentioned illustrious prophets. On the flipside, there has been a historic tendency of colonialists labelling their Muslim adversaries and anti-colinial movements as Mahdi-claimants to diminish popular support. [12]On the topic of Mahdi claimants, the great north Indian Sufi, Haji Imdadullah Muhajir Makki is recorded to have said in a malfuz: “Many people claim to be the Mahdi and this is something that people have done in the earlier days. Some people are complete liars and some are excused (ma‘dhur).” He also said that the claimants who excused are mistaken in thinking that they are the Mahdi while engrossed in meditation (muraqaba) of the names of Allah Most High (sayr-i-asma), specifically the … Continue reading

Interestingly, Bardoli also discusses this letter in his Gujarati account. According to Bardoli, Miya ‘Abdur Rahman claims not to have come with four bodies from the fourth sky but rather with the light (nur) of the above-mentioned four (Bardoli, 2011).

Letter from Mandvi’s raja

Crow spent the Wednesday and the following day (Thursday 18 January) collecting information “which all bespoke the determined resolution of the fanatic, and the hearty concurrence of his brother Mahometans to try a revolution here, when I received to take the sudden step of seizing him.” He also received a letter from three courtiers on behalf of Mandvi’s Raja Durjun Singh asking for military assistance and saying they would pay “six annas in every rupee of revenue annually” accrued from the princely state (Aitchison, 1864). In their letter they wrote:

“A Fakeer named Ubdul Raymaun (‘Abdur Rahman), who resides at Bodhan village, has been breeding rebellion by exciting the fanaticism of the Mahomedan religion, and assembling the Mussulmans, Bohrahs etc., of all the surrounding pergunnahs (district sub-divisions), and attempting to force the Brahmins to become Mahomedans; he has also erected the flag of Islam and taken possession of Mandavee, and burned down our houses with those of the ryots (tenant farmers), and plundered to the amount of lakhs of Rupees from the treasury of the Rajah, and also to the value of lakhhs of Rupees in money and jewels of the ryots.”

The letter adds that the Bohras have “usurped our country without justice” and that Muslims employed in the army of Mandvi had also joined them. This is probably in reference to the Arabs who had joined Miya ‘Abdur Rahman. They then ask for military help saying:

“Whatever charges may be incurred by sending the detachment shall be defrayed by us, and repaid by us to you on our retaking possession thereof; and if we fail to give a satisfactory answer for the above mentioned disbursements, the revenue of our territory shall be answerable for the demand.” [13]British records say that the raja agreed to pay an annual tribute of 60,000 rupees in lieu of a share of the revenues. However, due to the “exhausted state of the country” he was not “required to pay the cost of the expedition” that amounted to 20,000 rupees or his arrears in tribute that had risen to over 450,000 rupees. (Aitchison, 1864)

In his version of the events, Bardoli adds that having taken control of Mandvi, several of Miya ‘Abdur Rahman’s followers remained there and that two of them—Hasan Manjra and Ismail Boga (or Goba)—styled themselves as kings (Bardoli, 2011). These names are not mentioned in Crow’s account.

Resolve to take action

Encouraged by the letter, Crow decided to take military action. Storming Bodhan by surprise was key and so two troops of cavalry of the 56th Regiment were despatched to proceed to Bodhan by night and arrest Miya ‘Abdur Rahman if they could or prevent him from escaping. The infantry, commanded by a Captain Cunningham, travelled behind. Addressing Colonel Alexander Keith who commanded troops in the Southern Division of Gujarat, Crow wrote:

“I find myself urged by the conduct of a set of Mussulman fanatics, who have killed the Vizier, and taken upon themselves the administration of Mandvie, to make this representation against them. The Rajah of Mandvie is a prisoner in their hands, and also the eldest son of his late Vizier, whose name was Sookanund. The deceased’s brother, by name Shevanund, and his second son Vidianund, have both fled here. The fugitives have claimed the protection of the Company, and from all circumstances I think it should be granted without delay. The fanatic, who is the head of the rebellion, maintains his seat in a Mosque, at Boodhan, about ten coss, on the opposite side of the river. [14]Coss is a unit of distance formerly used in the Indian Subcontinent He is called Ubdul Rehman. From the dangerous tendency of Mahometan fanaticism in this country, and the correspondence which he has already extended to me, and to others, I think no time should be lost in reducing him. He has about seventy-five Arabs with him, and about two hundred more are at Mandvie, which is beyond Boodhan, nearly the same distance. It is advisable that a party of horse should be dispatched without delay, to seize the faquir, and another party of infantry with guns, to take possession of Mandvie. The rajah should be sent it in as soon as Mandvie may be taken, and the commandant of the detachment, assisted by Dhunjee Shah Behramund Khan, remain in charge till further orders.”

The showdown

It was daybreak on Friday 19 January 1810 that the cavalry arrived on the opposite bank of the Tapi. It would seem that the cavalry consisted of around 80 personnel while the infantry, which was still yet to arrive, were 400 to 800 soldiers. Though there was a Bengal Native Infantry known as the 56th Regiment that was operational in British India during the 19th century, there was also a European 56th Regiment of Foot that was active in India from 1755 to 1881. It is likely that it was the European 56th that was involved in the storming of Bodhan as Europeans would be normally used to put down rebellions, especially in an assault like this that involved attacking simple villagers. An infantry regiment originally raised in Northumbria, the 56th were seasoned soldiers having seen action in several conflicts of that time. This included Cuba during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), the Great Siege of Gibraltar (1779-1783) during the American Revolutionary War, and also in the Caribbean and Holland during the French Revolutionary Wars (1798-1802).

The records show that Miya ‘Abdur Rahman and his followers were in a mosque and that it was Dhanjish Behramund Khan, a notable Parsi aged around forty and native agent of the vassal states of Sachin, Bansda, Mandvi and Dharampur, who was first across the Tapi. Accompanying him was a representative of Mandvi’s raja and four scouts. Having crossed the bridge, Dhanjish “endeavoured to prevail on the fakir to surrender himself without a vain resistance” (Sharma & Sharma, 2004). Another writer picks up the story saying, probably with some exaggeration, that “he had scarcely communicated with the insurgents, when swords had leaped from their scabbards and dispatched the diplomatist on the longer and graver mission of eternity” (Briggs, 1849). Killed along with the native agent was the Raja’s representatives and scouts. [15]Briggs also writes that the East India Company paid Dhanjisha’s widow an annual pension of three thousand rupees “to maintain the appearances and dignity of his house.”

Crow continues the story. “A furious engagement ensued between the people and troops, in which the former had recourse to every species of sorcery and madness, and left nearly two hundred dead on the field.” What this “sorcery and madness” was is unclear, but perhaps there is a clue to this in what Sufi Sulayman narrates later on. The Asiatic Annual Register (Campbell & Samuel, 1812) describes the battle in colonial hyperbole in the following way:

“This brought on a furious engagement between the troops and the rabble, assembled under the colours of the impostor, which continued for some time, and was encouraged by all the arts resorted to in such enterprises, by religious hymns and incantations, which were sung by deafening din, stimulated by a raving bigot, and maddened by intoxicating drugs; but the resistance, after raging for a while, and producing a partial but temporary mischief, gave way, in the regular course of things, to the steady courage, and disciplined efforts of the organized troops; who put an end to the mad enterprise, by the dispersion of the populace, and the death of their deluded leader.”

Crow continues, “The cavalry lost a corporal and two privates, and several horses, and saw the town in flames when they came away. Shortly after their departure, the infantry, under Captain Cunningham, renewed the attack, to the destruction of many more, and amongst them the fanatic himself, Ubdul Rehman, who had been wounded by the dragoon, and taken refuge, with several more, in a blacksmith’s hut. The Rajah had been two or three days confined by him, but had made his escape the morning of the attack, it was not known whither.” The 56th Regiment, thereafter, was “ordered on to Mandvie, and the religious commotion was, by the death of Ubdul Rehman, totally allayed.”

Crow, who remained in Surat, learned of the fall of Mandvi and that the raja had been reinstated a few days later on 22 January. “General Abercombie [16]General Sir John Abercromby or Abercrombie (1772-1817) arrived in Surat on 22 January, presumably from Mandvi. Abercromby was a seasoned soldier having spent five years in a French prison when war broke out between Britain and France in 1803. On his release in 1808 he was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Bombay Army in 1809. During his career in the army he saw action in Flanders, the West Indies, Ireland, the Batvian Republic, Egypt, Mauritius and also India. He was widely decorated and … Continue reading arrived about four o’clock in the afternoon of the day,” writes Crow. Abercombie, who presumably arrived from Mandvi, was the Commander-in-Chief of the Bombay Army. A seasoned soldier, he had spent five years in a French prison and saw action in numerous countries. Crow continues, “The reports before mentioned were soon confirmed, with accounts of the Arabs having fired the town, and gone off with much treasure. The 56th Regiment was ordered in with the two eighteens, and the Rajah invited to accompany them.” Crow adds that Durjun Singh visited him on 28 January. He also, amusingly, described him as “about five and third, of large bulk, with much good nature, and few words.”

In Bardoli’s account, it is alleged that en route to Bodhan, the 56th regiment were attacked by villagers from Kosadi. This, however, is unlikely as Kosadi is situated north of Bodhan whereas the Company troops approached from the south. Bardoli also mentions that by the time Company troops arrived in Mandvi, Hasan Manjra and Ismail Boga (Goba) had already left (Bardoli, 2011).

Sufi Sulayman’s version

While Crow’s version of events could be assumed to be the most accurate due to it being a record by a contemporary who had intimate knowledge of the incident as it developed, we can never be sure whether it is accurate. There is, however, a different, yet interesting, narrative mentioned in Bagh-i-‘Arif. Published some 120 years after the incident in the 1930s, Bagh-i-‘Arif quotes Sufi Sulayman who as mentioned above may well have been alive in 1810 but only a child at the time and certainly not present. Sufi Sulayman is quoted to have said:

“The British sent an army from there [Surat] armed with cannons. However, the cannons and guns could not affect them, and their [the people of Bodhan] canes and bamboo sticks worked perfectly like swords. In the end, the British asked the ‘ulama whether he is the awaited Mahdi. They replied saying no, he is an ‘amil faqir. They then showed a way of overcoming him by allowing beautiful and pretty Hindu damsels to be left to go into that area and to fire the flesh of swine from cannons. It was, hence, done like this. Unfortunately, adultery finally began to take place and they were like this repelled. They became helpless and defeated, and many of them were arrested and punished…”

In his version of events Crow alludes that in the height of the assault on Bodhan the people of the village “had recourse to every species of sorcery and madness…” Could this be a reference to sticks working like swords, a miracle (or khariq al-‘adat), as mentioned in Bagh-i-‘Arif?

Was the Company heavy handed?

Whether what took place in Bodhan in 1810 was a revolt or an insurgency is open to debate. Fundamentally, Miya ‘Abdur Rahman was not of sound mind and, according to Sufi Sulayman, overcome by spiritual rapture (jazb). Anyone who knows Gujaratis would realise that the people gathered around him probably resembled a Dad’s Army and were definitely not up to the job of sedition and revolt. Perhaps, negotiations involving ‘ulama from the well-established scholarly families in Surat and diplomacy using familiar faces may have resulted in a less bloody outcome. These were not hardy Pathan tribesmen from the north but simple farmers in rural Gujarat. The East India Company’s behaviour, including using battle-hardy troops that had seen battle in several theatres of war of that time, was heavy handed—Bodhan was left in flames as the troops left with hundreds dead. There was no enquiry into what took place and certainly no other contemporaneous records that could shed light on the other side of the story or tell the story of those who died and their families. The only thing we really have is the account of the East India Company who had their own vested interests – history is written by the victors. Amidst this fog of history, what is, however, clear is that what took place was a tragic massacre. This is also something alluded to by the Asiatic Annual Register:

“The end of this commotion might not, perhaps, have been so tragical, if more timely means had been adopted for its suppression. The sword, the last resort of regular warfare, should often, we will not say always, be the first in insurrectionary tumults. Prompt, though severe measures, are more merciful often in their issue, than temporizing, irresolute proceedings, which afford a sort of parley, in a case that seems to demand an instantaneous decision.” (Asiatic Annual Register, 1810-11, 1812)

What happened afterwards?

So what happened to Surat’s Bohras? It would seem that they went back to doing what they are renowned to do well—making money. In his 1965 book on messianic movements in India, Fuchs writes about the 1810 incident and then comments in the following way, though one wonders if they ever did have hope for political supremacy (Fuchs, 1965):

“The Bohra burned their hope for political supremacy in Gujarat and in future concentrated on the acquisition of wealth by trade and other peaceful means. In this they were quite successful. Though originally a predominantly agrarian community, they have risen in status in recent years, and today they are among the most prosperous and numerous trading communities of Gujarat.” [17]Stephen Fuchs (1908-2000) was an Austrian Catholic priest, missionary and anthropologist who lived in India and researched the ethnology and prehistory of India.

And what about Miya ‘Abdur Rahman? British sources say that he was killed in the assault on Bodhan. Sufi Sulayman, however, says that he survived and “went into hiding from there.” He also adds that he lived for a long time, that he met him and that Hindus in his time still remember the incident in Gujarati songs, such as the following:

Chahsat na sal ma din jaga re Rama

Pehla Musalman din pukare re Rama

In the year 66, the religion (din) was awakened, oh Ram

Muslims were first calling out din, din, oh Ram

Kamri ne talware kappa re Rama

Chahsat na sal ma din jaga re Rama

Bamboo sticks cut through swords, oh Ram

In the year 66, din was awakened, oh Ram [18]The year 66 is in reference to the year 1866 according to the Hindu calendar which corresponds to 1810. These lines were transliterated in Bagh-i-‘Arif in Urdu script. The translation was provided by my late father, Haji Mohammed Ismail Nakhuda (d.2016), who also kindly explained the meaning.

Bibliography

Aitchison, C. (1864). Treaties, Engagements, and Sunnuds Relating to India and Neighbouring Countries (Vol. Six). Calcutta: O.T. Cutter, Military Orphan Press.

Asiatic Annual Register, 1810-11. (1812).

Briggs, H. (1849). The Cities of Gujarashtra, Their Topography and History Illustrated. Bombay: Times Press.

Campbell, J. M. (1879). Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency (Vol. Two). Bombay: Government Central Press.

Campbell, L. D., & Samuel, E. (1812). The Asiatic Annual Register (1810-1811). London.

Fuchs, S. (1965). Rebellious Prophets – A Study of Mesianic Movements in Indian Religions. New York: Asia Publishing House.

Hamilton, W. (1828). The East-India Gazetteer (Vol. Two). London: WM. H. Allen and Co.

Misra, S. (1964). Muslim Communities in Gujarat. London: Asia Publising House.

Sharma, K. S., & Sharma, U. (2004). Cultural and Religious Heritage of India: Zoroastrianism. New Delhi: Mittal Publications.

The Asiatic Annual Register 1801. (1802). London: Wilson & Co. Oriental Press.

References

| 1 | A note on transliteration. Colonial-era spellings are invariably inconsistent. The name ‘‘Abdur Rahman’ may appear as ‘Ubdal Rehman’ and also ‘Ubdal Rahman.’ Likewise, the word ‘fakir’ is transliterated as ‘faquir’ and also ‘fakir.’ I have retained colonial spellings in quotes to ensure the language remains as close to the original sources as possible and at places included a more acceptable transliteration in brackets. |

|---|---|

| 2 | The Bhils are an ethnic group found in western India and considered the indigenous people of the states of several states, including Gujarat. The Bhils rebelled on several occasions during the colonial period and were designated as a criminal tribe by the British Indian Empire under the Criminal Tribes Act 1871. In modern India, the Bhil are classified as a Scheduled Tribe. |

| 3 | The State of Mandvi functioned until 1839 when the direct line of succession became extinct and the state was thereafter treated as an escheat and annexed to the British dominions. |

| 4 | The Sunni Bohras (also known as Vohras) are several traditionally endogamous Muslim communities found in Gujarat. Though some ethnographers (Misra, 1964) claim they are primarily agrarian communities that converted to Islam, it would, seem that they are of mixture of ancestry – some may have certainly converted while others are descendants of foreign Muslim groups (Arabs and Persians) who over the centuries settled in Gujarat. Misra identifies several regional sections of the Sunni Bohras such as the Patni Bohras, Kadiwal Bohras, Charotar Bohras, Surti Bohras and the Patel Bohras also known as the Bharuchi or Kanamia Bohras. The Bohras referred to in this paper are the Surti Sunni Bohras. There is also a prominent Shiite Bohra community in Gujarat known as the Dawoodi Bohras from whom several other groups have branched out, including the Sulaymani Bohras and the Aliyah Bohras. |

| 5 | Pardi, also called Kila Pardi, is home to a fort (kila or qil‘ah) built by the Maratha warrior-king Shivaji (d.1680). |

| 6 | It is most likely that the Arabs referred to here were Hadhrami mercenaries from Yemen who were known to have taken up military roles under various Indian rulers during this period. Though Arabs entered Gujarat as traders before the Muslim period, there are no traces of the early Arabs (Misra, 1964). Misra writes that the Arabs found when he carried out his research came mainly in the 18th century to enlist into the forces of Indian princes. |

| 7 | Deepak Bardoli is the penname (takhallus) of Musaji Yusufji Hafiz of Bardoli. His book, Sunni Vohra Samaj Tarikh keh Aina, includes a short write up of what took place in Bodhan in 1810. Written in Gujarati, I am grateful to Mawlana Ismail Kawthar Kawthari (a resident of the village of Kosadi in Surat) who sent me an Urdu translation of the relevant sections. |

| 8 | According to late 19th century British sources, Bodhan was a place of Hindu pilgrimage and had a population then of 3,305 (Campbell J. M., 1879). |

| 9 | Sufi Sulayman Diwan was a Sufi of the Naqshbandi and Shadhli orders from the village of Lajpur, Gujarat. He received khilafah from Shaykh Nizamuddin Mujaddidi (d.1866) of Bajaur (situated in what is today the Malakand Division of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in Pakistan). Shaykh Nizamuddin lived and died in Tadkeshwar, Surat, and was also the shaykh of Haji Musaji Mehtar (d. circa 1891), the famous Naqshbandi Sufi of Tadkeshwar. During a trip to the Hijaz, Sufi Sahib received khilafah in the Shadhli Idrisi order from Shaykh Ibrahim al-Rashidi (d.1874) in Makkah who himself was the khalifah of Shaykh Ahmad ibn Idris al-Fasi (d.1837) who counted among his students the Grand Sanusi Shaykh Muhammad ibn Ali al-Sanusi (d.1920). Sufi Sulayman also received khilafah from the great north Indian hadith scholar Mawlana Fadhlur-Rahman Ganj Muradabadi (d.1895). During his life he met a number of senior scholars and Sufis, including Hakim al-Ummah Mawlana Ashraf Ali Thanawi (d.1943) as mentioned in Ashraf al-Sawanih, Haji Warith Ali Shah (d.1905) of Dewa, UP, and Maulvi Liaqat Ali (d.1892) of Allahabad, a scion of the 1857 Indian Mutiny who was imprisoned in the Andaman Islands (Kala Pani). He also debated with Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Qadiani (d.1908). In 1917, Sufi Sulayman purchased land close to the railway station in Surat where he built a mosque, living quarters and a madrasah known as Madrasah Sufiyyah. After a lifespan of over a hundred years, Sufi Sulayman passed away in 1924 and was buried close to the mosque he built. The mosque and madrasah he founded still exist today and the entire area is known as the Sufi Bagh (Sufi Garden) area of Surat. |

| 10 | Bagh-i-‘Arif is attributed to Sufi Sulayman and was originally published in 1937 by Khilafat Press, Bombay. Compiled by his son, it also includes a short but interesting biography of Sufi Sulayman in which the 1810 incident in Bodhan is mentioned. A new edition of this book was published by Majlis-e-Dawatul Haq, Leicester, in 2007. |

| 11 | Sayyid Muhammad Hada and his brother Sayyid Ahmad Hada are mentioned in the Haqiqat al-Surat, a Persian biographical dictionary of the 18th and 19th century by Shaykh Bakhshu Miya (d.1849) and his son Shaykh Shaykhu Miya (d.1911). The version I have before me is an Urdu translation by Professor Mahbub Hussayn ‘Abbasi published by the Gujarat Urdu Academy (published in 2005). According to Haqiqat al-Surat, Sayyid Muhammad Hada was from the Qadri family of sayyids, whose saintly ancestors were awarded the village of Valan, most likely in Baroda, by one of the Mughal emperors. The sayyid was a learned individual and excelled in logic and other sciences. He was also employed at the High Court in Surat (‘adalt-i-‘aliyyah) as a molwi. |

| 12 | On the topic of Mahdi claimants, the great north Indian Sufi, Haji Imdadullah Muhajir Makki is recorded to have said in a malfuz: “Many people claim to be the Mahdi and this is something that people have done in the earlier days. Some people are complete liars and some are excused (ma‘dhur).” He also said that the claimants who excused are mistaken in thinking that they are the Mahdi while engrossed in meditation (muraqaba) of the names of Allah Most High (sayr-i-asma), specifically the name of Allah Al-Hadi (the guide). “This is because in the meditation of the name Al-Hadi when the salik is overcome with the brightness of the name Al-Hadi then he begins to think he is the Mahdi…” he said. Sufi Sulayman felt that Miya ‘Abdur Rahman was in spiritual rapture (jadhb) and it could, therefore, well be the case that he was a sincere Sufi who had lost his senses (or turned majdhub) while treading the spiritual path. Qari Muhammad Tayyab, the Rector of Dar al-‘Ulum Deoband, writes in his Maslak-i-‘Ulama-i-Deoband: “The methodology of the shaykhs of Deoband in regards to this balanced maslak and the spiritual states (hal) of Tasawwuf has always been that they never embroil themselves with the majdhubs or those who are not with their senses due to being overcome by a spiritual state, nor do they denounce them. Rather, they leave them as they are and stay aloof from them…” |

| 13 | British records say that the raja agreed to pay an annual tribute of 60,000 rupees in lieu of a share of the revenues. However, due to the “exhausted state of the country” he was not “required to pay the cost of the expedition” that amounted to 20,000 rupees or his arrears in tribute that had risen to over 450,000 rupees. (Aitchison, 1864 |

| 14 | Coss is a unit of distance formerly used in the Indian Subcontinent |

| 15 | Briggs also writes that the East India Company paid Dhanjisha’s widow an annual pension of three thousand rupees “to maintain the appearances and dignity of his house.” |

| 16 | General Sir John Abercromby or Abercrombie (1772-1817) arrived in Surat on 22 January, presumably from Mandvi. Abercromby was a seasoned soldier having spent five years in a French prison when war broke out between Britain and France in 1803. On his release in 1808 he was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Bombay Army in 1809. During his career in the army he saw action in Flanders, the West Indies, Ireland, the Batvian Republic, Egypt, Mauritius and also India. He was widely decorated and also made an MP for Clackmannanshire. |

| 17 | Stephen Fuchs (1908-2000) was an Austrian Catholic priest, missionary and anthropologist who lived in India and researched the ethnology and prehistory of India. |

| 18 | The year 66 is in reference to the year 1866 according to the Hindu calendar which corresponds to 1810. These lines were transliterated in Bagh-i-‘Arif in Urdu script. The translation was provided by my late father, Haji Mohammed Ismail Nakhuda (d.2016), who also kindly explained the meaning. |

Massahallah quite interesting history which is not in my knowledge allahsubanatalla give you rewards.

MashaAllah

Allah reward you for your hard work

Very nice please send documents this information?

MASHA-ALLAH

Assalamalaikoum Ismaeel bhai

Very interesting research

I am interested in all aspect of gujarat history and particularly on Gujarati diaspora in Reunion island and Mauritius

Im a retired librarian (i worked at the university library in reunion island where live)

I visited Bodhan the ancestral village of my father-in-law several times in the last years

At each of our trip, we used to visit the kabar of Safla’s family ancestors in Bodhan. And we were very surprised to discover in the kabrasthan of Bodhan a ´tumulus’ near a wall. We have been said by older people of Bodhan that it was the kabar of hundred of shahid fighters who were killed by the English during a revolt. There is no funerary stele near by, nothing to recall for which fight these ‘shahid’ died

Is there a link with this 1810 revolt ?

Later on i discover there had been a revolt in 1810 in Bodhan thanks to the book of Edalji Dosabhai “A history of Gujarat : from the earliest period to the present time” (1894). (the revolt from the hindoo point of view ) Please send your email so I can send you the scan of the few pages on the revolt of 1810 in this book.

Waiting for your reply

PS : Note that the French researcher Marc Gaborieau did a lot of researches on mahdism movment in indian subcontinent in 19th

Wa alaykum salam Sister, thank you for the message. Very interesting. I have messaged you. Jazakallah khayra for reaching out and sharing this information. Ismaeel

Very interesting

Assalamoualaikoum to All of You,

I have been to India several times both for business and researching my roots. The word Nakhuda means Captain of a ship, The word Bham is the word used to measure depth of the ocean or river. I have been to Rander and it is a very fascinating place. The Iraqis who captured the land from the Jain “third biggest religion in India”, Guju muslims are mixed blood from Turkey, Yemen, Brahmans. Iraqi, Parsee and a trace of Portugese. Some of the prominent families from Rander came to Mauritius in 1800, such as Boatawala, Angulia, Piperdee and then they left because Mauritius was too small for trade and they moved to Bangkok and Singapore etc. A lot of business families from Rander went bankrupt when the Junta took over in Rangoon and nationalised everything such as Nakhuda , Aref families.

Rander was known as city of Mosques and has the highest density of mosques in the world, some of the architecture is amazing, The Bawan family that came to be known as Bawamia built a mosque that fascinates architects up to these present days.

I would recommend you to send your kids to visit Surat.

Allah Hafiz

Osman.Bharoocha

Montreal

A superbly written, historical anthology of a much forgotten part of Indian Islamic history. The quality of your language and the themed approach, along with the depth of research is to be admired. You should look to getting this published in scholarly journals.

Well done and hope you’ll delve further into the history of Sunni Bohra communities in Gujarat and Sufi saints.

Vahoras, including the coastal ones, are likely local converts. There were no large endogamous foreign muslim settlements recorded in history. Vahoras were following many primitive hindu practices before the relatively recent change to Islamic practices in the past ~150 years. The local population in gujarat included many parsis (mostly farmers) who were known to be persecuted by muslims, so that’s where our strange appearances probably come from.

Jazakallah khayra for sharing your views, my views are as mentioned in footnote 4. There are several reasons why I feel this is the case, will insha Allah write on this one day. Thanks for the comment.

Jazakallah for the response, I am going off of genetic evidence from the G25 principal component analysis, as well as y-chromosomal evidence off of relatives on 23andme (J2 heavy), and combining it with extensive historical knowledge. The ancestry component I find usually fits best with Fars province and seems to peak in Bharuchies based on mathematical investigation. I’ve wrote about this in a few places including here (https://genoplot.com/discussions/post/574727) and here (https://genoplot.com/discussions/topic/26759/created-harappaworld-like-calc-in-g25/71), I should do a more extensive combination of all the evidences later but usually don’t find the time.

Y-chromosome clustering will definitely solve this soon, once more people get full genome or tested with Big-Y and upload their results to y-full, we will find the true origins.

I did some more updates to the gujarati muslims and sunni vohras wiki articles to include more evidence regarding middle eastern settlements in gujarat and also regarding parsi conversions in south gujarat. I still personally think parsis are the likely ghost for our ME ancestry given our very previous hindu-ish practices including praising hindu gods on occasions like marraige. There were definitely strong middle eastern settlements but endogamous but I still do believe Parsi conversion is more dominant source for the sunni vohras of source gujarat.

Jzk

Last sentence should have been:

There were definitely strong middle eastern settlements but they rarely remain endogamous, let along endogamous + adopt hindu practices + forget origin. Everything magically fit once I considered the Parsi convert hypothesis, so I still do believe Parsi conversion is more dominant source for the sunni vohras of source gujarat.

Jzk

Also one of the other interesting incredible evidences I found worth mentioning, if you look at the old parsi documents from the surat and navsari villages, they also called themselves “Vohras”. Check out “studies in parsi history”

Jzk

Provide evidence to the assertion that the Surti Muslim are Hindu in origin ?

You can trivially get your dna tested and upload it to gedmatch and run harappaworld admixture, or get G25 and run nmonte monte carlo simulations. Arab ancestry is clearly distinguishable since it has very different ancient components than South Asian. Persian ancestry is harder to distinguish because there are more overlaps, but it can be done if we assume Surti Vohra = + , and check the result.

We do not seem to be arab since it’s mostly J2 heavy in terms of the foreign ancestry, which indicates persian ancestry. There may still be some arab but it is likely quite small if it exists.

Part of the comment didn’t show up correctly due to markup, so reposting:

You can trivially get your dna tested and upload it to gedmatch and run harappaworld admixture, or get G25 and run nmonte monte carlo simulations. Arab ancestry is clearly distinguishable since it has very different ancient components than South Asian. Persian ancestry is harder to distinguish because there are more overlaps, but it can be done if we assume Surti Vohra = Gujarati Populations + Persian, and then check the result and how good the model fit is.

We do not seem to be arab since it’s mostly J2 heavy in terms of the foreign ancestry, which indicates persian ancestry. There may still be some arab but it is likely quite small if it exists.

Deep cluster and mass knowledge about my village Bodhan, when I read this artifact, my self indulge in that era of time, like whole film of imaginations was operated in front of my eyes, very spectacular, cavernous, profound history of Bodhan village. I am pasture, grassland, meadow that I am belong to Bodhan.