By Mufti Zameelur Rahman

According to an established and widely-known ḥadīth, the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) was affected by siḥr (sorcery) causing him to fall ill and imagine having done things that he did not do. The ḥadīth is found in the Ṣaḥīḥs of al-Bukhārī and Muslim, amongst other books, and has been accepted unquestioningly by the scholars of Ahl al-Sunnah wa ‘l-Jamā‘ah. In premodern times, the only significant opposition to the ḥadīth came from the deviant non-Sunnī group of the Mu‘tazilah, based principally on their adherence to a type of materialist philosophy that does not allow for paranormal influences having any effect in the material world. With the spread of a similar such philosophy in the western world in the 19th century CE, and the subsequent influence of western thought in the Muslim world, modernist Muslim intellectuals began to deny this ḥadīth also.

The Mu‘tazilah of old of course spelled out some “reasons” for denial of the ḥadīth which were thoroughly and robustly dismantled by the scholars of Ahl al-Sunnah. Modernist arguments do not represent any significant departure from the old, rehashed arguments of the Mu‘tazilah. The famous Egyptian muḥaddith, Shaykh Aḥmad Shākir (1892 – 1958 CE), says of this ḥadīth:

“Many people of our era have targeted this account with denial. In their denial, they are imitators, while they claim to be guided by their intellects. Others have preceded them in this, and the scholars have refuted them.”[1]

The contemporary muḥaddith, Shaykh Muḥammad ‘Awwāmāh, writes on the same ḥadīth:

“Premodern and modern innovators have contemptible speech on this and other ḥadīths on the topic…What our earlier scholars said in response to those innovators, the very same can be said in refutation to these ones.”[2]

Ibn al-Qayyim says of the ḥadīth in question:

“This ḥadīth is established according to the holders of knowledge in ḥadīth, and it has been received with acceptance amongst them and they do not differ over its authenticity…The authors of the two Ṣaḥīḥs have agreed on authenticating this ḥadīth, and none of the experts of ḥadīth spoke against it with a single word. The account is well-known amongst the experts of exegesis, traditions, Ḥadīth and history, and [amongst] the jurists. They are more learned of the conditions and times of Allāh’s Messenger (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) than the mutakallimīn [who have denied the ḥadīth].”[3]

Qāḍī ‘Iyāḍ says of the ḥadīth: “The ḥadīth is ṣaḥīḥ and agreed-upon and [only] heretics assault it.”[4]

Amongst the contemporary modernists who have rejected this ḥadīth, one prominent figure is Dr Akram Nadwi. He has written an Arabic piece on the topic[5], and had also delivered a talk on it in English alongside Nahiem Ajmal (Abu Layth) in 2017. His arguments are essentially a recycling of old-Mu‘tazilī arguments, including the perspective that siḥr is essentially “of an illusory nature”. Although he does add some new “reasons” for rejecting the ḥadīth, these are so contrived and so obviously fallacious that one will be justified in believing that Dr Akram Nadwi himself does not take them seriously i.e. that his “academic” case is disingenuous. Dr Akram Nadwi’s arguments against the ḥadīth can be summarised as a) emotional arguments, b) pseudointellectual arguments and c) a methodological case for the practice of rejecting authentic ḥadīth. These will be tackled in turn below.[6]

In the course of the refutation, it will be demonstrated how lacking in substance the modernist rejection of this ḥadīth is, and more importantly, how someone following the misguided modernist methodology Dr Akram Nadwi espouses can potentially be convinced of anything that goes against the accepted teachings of Islām while disingenuously pointing to some contrived reasons. The consequences of such methodology are of course very dire, and could potentially lead to denial of fundamental aspects of Islām.

We hope the following refutation will serve to expose Dr Akram Nadwi’s modernist approach and how critically irrational and dogmatic it is, which should cause the reader – even if for purely academic reasons and not religious ones – to question whether Dr Akram Nadwi’s research or claims can ever be trusted.

Before tackling Dr Akram Nadwi’s points, we will take a look at the ḥadīth and its sources.

The Ḥadīth

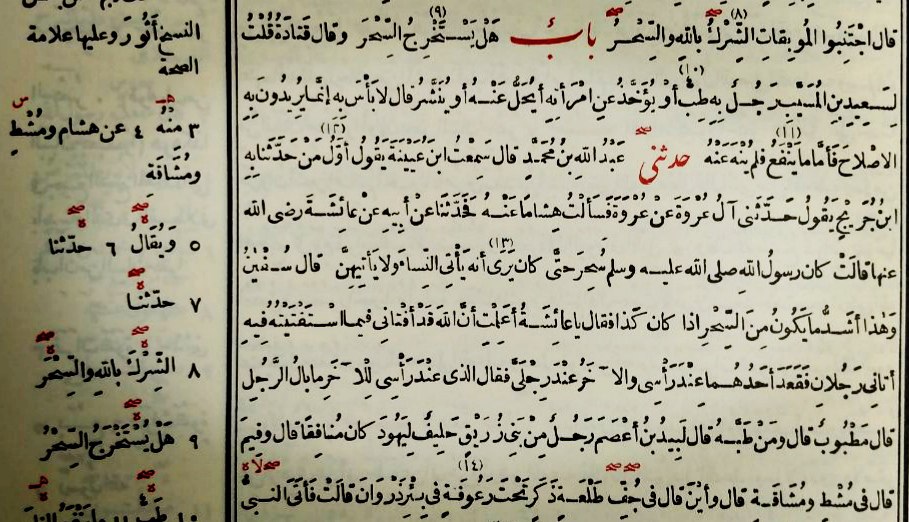

The most famous version of the ḥadīth comes from ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her). In the ḥadīth, ‘Ā’ishah reports that the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) came under the influence of siḥr and began to sense or feel things that were not real; he supplicated to Allāh repeatedly, and then – as he would later inform her – two angels came to him and sat by him, informed him that Labīd ibn A‘ṣam had performed siḥr on him, and the magic was contained in some strands of hair on a comb wrapped inside the outer skin of the spadix of a date-palm, and hidden in a specified well; after the material was extracted and the siḥr neutralised, the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) found relief.[7]

From ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her), one of her most prominent and learned students, her nephew ‘Urwah ibn al-Zubayr (23 – 94 H), reports it. From ‘Urwah, his son Hishām ibn ‘Urwah (61 – 146 H) reports it. Both ‘Urwah and Hishām are accepted authorities in ḥadīth. Some of the experts on ḥadīth have even considered the chain Hishām from ‘Urwah from ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her) to be the most reliable chain to ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her).[8]

The following reliable imāms narrated it from Hishām ibn ‘Urwah:

- Sufyān ibn ‘Uyaynah (107 – 198 H), the major Makkan imām [9]; Imām al-Shāfi‘ī narrates this ḥadīth in his al-Umm from Sufyān ibn ‘Uyaynah[10]

- Al-Layth ibn Sa‘d (94 – 175 H), the major Egyptian imām [11]

- Abū Ḍamrah Anas ibn ‘Iyāḍ (104 – 200), a Madīnan imām of ḥadīth [12]

- ‘Īsā ibn Yūnus (d. 187 H), a prominent muḥaddith of Kūfah [13]

- Yaḥyā ibn Sa‘īd al-Qaṭṭān (120 – 198 H), an unparalleled expert in ḥadīth from Baṣrah [14]

- ‘Abdullāh ibn Numayr (115 – 199 H), an imām of ḥadīth from Kūfah [15]

- Ma‘mar ibn Rāshid (95 – 153 H), a major Baṣran imām of ḥadīth [16]

- Abū Usāmah Ḥammād ibn Usāmah (121 – 201), a prominent muḥaddith of Kūfah [17]

- Wuhayb ibn Khālid (107 – 165) of Baṣrah [18]

- ‘Alī ibn Mushir (ca. 120 – 189 H) of Kūfah [19]

These are major transmitters from Makkah, Madīnah[20], Egypt, Baṣrah and Kūfah. Most of the above transmissions are recorded in the Ṣaḥīḥs of al-Bukhārī and Muslim.[21] While Hishām, as an authoritative transmitter of ḥadīth, is entirely dependable on for this narration, even still, there were apparently other members of the family who would also narrate this ḥadīth from ‘Urwah. Sufyān Ibn ‘Uyaynah in his transmission of the ḥadīth explains: “The first to narrate it to us was Ibn Jurayj, saying: ‘The family of ‘Urwah narrated to me from ‘Urwah’, and then I asked Hishām about it and he narrated to us from his father from ‘Ā’ishah…”[22] Ḥāfiẓ Ibn Ḥajar comments that this shows that others besides Hishām also apparently narrated it from ‘Urwah.[23] Moreover, Hishām makes it clear in one transmission from him that he received this directly from his father ‘Urwah without any intermediary[24]; thus, the alleged flaw of occasional intermediary-dropping (tadlīs) from Hishām cannot be brought as an objection here. In the version of Layth ibn Sa‘d, it is also made clear that ‘Urwah “heard it and comprehended it from ‘Ā’ishah”.[25]

Ma‘mar ibn Rāshid (95 – 153 H) narrates in his Jāmi‘ from Ibn Shihāb al-Zuhrī (58 – 124 H) from both Sa‘īd ibn al-Musayyib (15 – 94 H), who was regarded by some as the greatest of the Tābi‘īn of his era, and ‘Urwah ibn al-Zubayr that Jews of Banū Zurayq performed siḥr on the Messenger of Allāh (peace and blessings be upon him) and kept it in a well.[26] This demonstrates that the famous muḥaddith of Madīnah, al-Zuhrī, also narrated this ḥadīth from ‘Urwah, albeit without mentioning ‘Urwah’s source (i.e. ‘Ā’ishah).

While the ḥadīth of ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her) is the most famous account, Zayd ibn Arqam (Allāh be pleased with him) also narrates it. Ibn Abī Shaybah reports:

“Abū Mu‘āwiyah narrated to us from A‘mash from Yazīd ibn Ḥayyān from Zayd ibn Arqam (Allāh be pleased with him) that he said:

“A man from the Jews performed siḥr on the Prophet (Allāh bless him and grant him peace), so the Prophet (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) became unwell on account of that for some days. Then Jibrīl came to him and said to him: ‘So-and-so man amongst the Jews has performed siḥr on you, and has tied knots over you.’ The Messenger of Allah (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) sent ‘Alī on account of this, who extracted it and brought it. Every time a knot was untied, he felt some relief. Then the Prophet (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) stood up as though released from some fetters. The Prophet (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) thereafter did not mention this to that Jew, nor did [the Jew] ever see this [i.e. registering it or showing displeasure for it] on his face.”[27]

The same narration with the same chain is reported by al-Nasa’ī in his Sunan, and Aḥmad in his Musnad.[28] Al-‘Iraqi said of this report: “Al-Nasa’ī narrated it with a ṣaḥīḥ chain from Zayd ibn Arqam.”[29]. Imām al-Ṭaḥāwī also narrates both versions of the ḥadīth – from Zayd ibn Arqam and ‘A’ishāh – to argue for the effect of siḥr.[30] Shaykh Shu‘ayb al-Arnā’ūṭ comments on the ḥadīth of Zayd ibn Arqam: “Its chain is [ṣāḥīḥ] according to the criterion of Muslim.”[31]

Given this, the incident is amongst one of the most well-established events in the life of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him). The ḥadīth of ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her) in the two Ṣaḥīḥs was received with acceptance and no muḥaddīth in all premodern history questioned its authenticity despite the two Ṣaḥīḥs being put under immense scrutiny. Moreover, there is the corroborating ḥadīth of Zayd ibn Arqam (Allāh be pleased with him), which has been regarded as authentic by some ḥadīth experts. Along with this, other narrations show that this was something known in the time of the Salaf. Thus, denial of this ḥadīth must stem from something apart from the reliability of its source.

We now turn to Dr Akram Nadwi’s reasons for denying the ḥadīth.

Emotional Arguments

In response to the question of whether siḥr was performed on the Prophet (peace and blessing be upon him), Dr Akram Nadwi writes in his Arabic piece:

My hair stands on end and my skin trembles at the horror and terror of this view, denouncing it strongly, finding it extremely repugnant. Do you realise where you [stand]? Do you comprehend of whom you are talking? About the most virtuous of Allāh’s creation and the most beloved of them to Him, about the Seal of Prophets and the Master of Messengers, about the Truthful, Trusted Prophet and the Recipient of the Clear Book, Allāh bless him and grant him peace.

In response to the point that this is what has been stated, he says:

Had only you fornicated, and perpetrated every despicable vile deed and ugly sin and great evil besides idolatry! Had you done that, it would be lighter than this repulsive, lowly, view, which the devil has brought on your tongue, making light of your intellects and mocking your ignorance and foolishness.

As stated above, the view that the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) did come under the influence of siḥr was effectively the consensus view of premodern scholars of the Ahl al-Sunnah wa ‘l-Jamā‘ah, based on well-documented evidence. Dr Akram Nadwi’s outburst here implies all of these scholars were guilty of a crime worse than everything apart from idolatry and were all misled by the devil! Such implications often arise from modernist and revisionist views such as the one Dr Akram Nadwi is here espousing.

He continues:

You have done wrong to the Master of the Worlds, in not maintaining etiquette with Him when you attacked His Beloved and the Crème of Creation.

Dr Akram Nadwi is here attempting to appeal to a Muslim’s deep loyalty and love for the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him), while not realising that by virtue of this very loyalty and love, Muslims know not to reject something established from him. To reject something that the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) has taught merely because it does not sit right with how we view him is to be disloyal to him. Someone whose loyalties truly lie with the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him), his hairs should stand on end at how someone claiming to be devoted to him so brazenly rejects what he has said and taught.

Addressing a similar emotional argument by the Mu‘tazilah against this ḥadīth, the early Kūfan scholar of linguistics and ḥadīth, Ibn Qutaybah (213 – 276 H), wrote:

“What is there to find objectionable in Labīd ibn al-A‘ṣam, this Jew, doing siḥr on the Messenger of Allāh, when Jews before him killed [the Prophet] Zakariyyā…and killed after him his son Yaḥyā?…They killed prophets, left them out in extreme heat and tortured them with [various] kinds of tortures. Had Allāh (Majestic and Mighty is He) wished He would have protected them from them; and indeed the Messenger of Allāh (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) was poisoned…And Allāh (Exalted is He) related from Ayyūb (upon him peace) that he said: ‘Satan has afflicted me with distress and torment.’” [32]

As Ibn Qutaybah mentions, the Qur’ān records that Jews had executed some prophets.[33] Why cannot someone in equal indignation to Dr Akram Nadwi say: “Do you know of whom you speak? Of prophets of Allāh and the greatest of His creation, being executed?!” Such emotional outbursts are of course senseless, irrational and ignorant.

Ibn Qutaybah also mentions here that the Qur’ān refers to the prolonged illness of the Prophet Ayyūb (upon him peace), and specifically that he attributed its cause to Satan.[34] As commentators of the Qur’ān have noted, this attribution to Satan can be interpreted literally or figuratively in this context.[35]

Dr Akram Nadwi presumably would not have any issues accepting the fact the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) fell ill, was injured, hurt, bruised and so on, and he does not believe these lessen the status of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him). The real issue for Dr Akram Nadwi therefore does not seem to be that the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) was unwell, but that he became unwell through an immaterial mechanism. This is precisely the Mu‘tazilī contention. But why should believing Muslims have any issues with accepting that Allāh has put immaterial, paranormal causes in operation in the world?

Dr Akram Nadwi probably believes there are tiny, invisible microbes that cause illnesses like the flu and malaria, an idea which the ancients would probably find unbelievable. Would one not find it difficult to imagine how such tiny, invisible things can wreak such havoc in the human body? But there are apparently no issues with believing this because science has told us so. Can we not at least have as much belief in our revealed sources as we do in science?! This is apart from the fact that the effects of the paranormal are attested to by widespread experience throughout civilisations and eras.

Imām Abū Sulaymān al-Khaṭṭābī (319 – 388 H) writes:

“Siḥr is established and its reality exists. Most civilisations, whether Arabs, Persians, Indians, and some of the Romans, agree on its reality…Allāh mentions the affair of siḥr in His Book in the story of Sulaymān, and what of it the devils learned and taught to man…and He ordered that we seek protection from it, saying: ‘[Say: I seek protection…] from the evil of those who blow in knots.’ Many reports on this have been transmitted from the Prophet (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) and from the Companions (Allāh be pleased with them), none denying them – on account of their abundance – besides someone who rejects the plainly visible and denies clearly evident knowledge. This is why the jurists derived rulings in their books related to sorcerers, and the punishments that are due on them for the acts they do…Something having no basis or no reality would not have reached this degree of fame and abundance. Negating [the reality] of siḥr is ignorance, and engaging in refuting one who negates it is futile and excess.”[36]

Imām Abu ‘Alī al-Māzirī (453 – 536 H) writes explaining the reality of siḥr:

“It is not rationally inconceivable that the Creator (Glorious is He) ruptures the normal occurrences when some jumbled statements are pronounced, or some items are put together, or faculties are mixed in a sequence known only to a sorcerer. One who has observed that some physical objects are fatal like poison, some are detrimental like harmful drugs and some are beneficial like medicines that combat illnesses, it will not be farfetched in his mind that a sorcerer has exclusive knowledge of faculties that are fatal or speech that is detrimental or that leads to separation.”[37]

As Imām al-Ghazālī has explained, siḥr is achieved by performing rituals normally blasphemous in nature or in violation of Sharī‘ah that drive devils to cause harm to somebody.[38] Why should Muslims – who are believers in Qur’ān and Ḥadīth, and are not materialists – object to this reality?

Pseudointellectual Arguments

The Disbelievers Say the Prophet (Peace be Upon Him) was Affected by Siḥr

Attempting to argue the ḥadīth opposes the Qur’ān, Dr Akram Nadwi writes:

Is not this despicable, lowly, statement from the essence of what the disbelievers and idolaters said, and Allāh refuted them strongly, finding their behaviour filthy? Do you not recite His statement in Sūrat al-Isrā’: “We know best what they were listening attentively to when they listen attentively to you and when they are in private conversation, when the wrongdoers say: ‘You are but following a man possessed (masḥūr)[39]!’ Look how they present examples of you and thus fall into error and find no path.” Do you not recite in Sūrat al-Furqān: “The wrongdoers say: ‘You follow only a man possessed (masḥūr).’ Look at how they present examples of you and thus fall into error and find no path.”?

He goes on to mention that Allāh refutes the claims of other disbelievers about their respective prophets being possessed.

This argument of Dr Akram Nadwi is also not new. It was one put forward by the original Mu‘tazilī rejectionists. In refutation of them, Imām Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī writes:

“As for their saying that the disbelievers would characterise the Messenger (upon him peace) as being possessed (masḥūr), so had that occurred the disbelievers would be truthful in this claim, the answer is that the disbelievers intended by him being possessed that he was insane, his intellect having been removed by means of siḥr and thus he abandoned their religion. As for him being affected by sīhr with a sickness he experiences in his body, that is something that no one finds objectionable. In sum, Allāh (Exalted is He) would empower neither a devil, nor a human nor a jinni, to harm him in his religion, Sharī‘ah or prophethood; as for causing harm to his body, there is nothing strange [about that].”[40]

Other exegetes have provided a similar explanation.[41] What it amounts to is that there are different kinds of siḥr. Some would only have an effect on the physical body, while others would affect the mind and cause the victim to become insane. The Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) was protected from the effects of the latter kind of siḥr, and it is this type of siḥr that the disbeleivers accused him of being under the influence of.

There are some types of physical illnesses that can cause a person to lose his mind and become insane also. Of course, the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) was protected from such physical illnesses, just as he was protected from siḥr that could affect his sanity or his preaching.

The claim of the disbelievers referred to in the verses in question is only of substance if the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) came under the influence of a siḥr that affects what he preached and taught; siḥr that only affects the physical body obviously does not fall under this category. Hence, the disbelievers are quoted as saying: “You are but following a man possessed,” that is, siḥr is influencing what he conveys to you and what you follow him in. The siḥr in question was not of this nature. The Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) is protected from the type of siḥr or illness that could make him say something incorrect; hence the siḥr did not, and could not, influence his teachings or what he preached to the people. Merely being affected by siḥr, just like merely being affected by illness, does not itself entail any effect in what he preaches. It just means he was a human being. The narration says nothing more than his being affected by the siḥr, making him ill and making him see and imagine things that were not there for some time. This is also possible from some forms of illness.

Later in the Arabic piece, while listing his reasons for rejecting the ḥadīth of ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her), Dr Akram Nadwi says the Jews would have capitalised on the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) being affected by siḥr to cast doubt on his prophethood; and since we have no record of this, this adds to the case for denying the ḥadīth. But it should be clear from the above that the type of siḥr that befell the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) is not the kind that would cast doubt on his prophethood. Hence, this too is a fallacious argument. In fact, as will be explained below, the incident of siḥr has been described by one of the scholars as being from “the strongest proofs of his prophethood”!

The Prophet (Peace be Upon Him) is Protected

Dr Akram Nadwi further argues:

Do you not know that Allāh has promised to protect him and safeguard him: “and Allāh protects you from people.” Do you not know that Allāh does not renege on His promise? Do you believe Allāh will leave His Chosen Prophet (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) for the rebellious devils, the deviant disbelievers and lawless sorcerers to play with him? Allāh is far above what the oppressors say!

One can equally say, why did Allāh not protect him against the viruses and parasites, germs and bacteria, which apparently caused his illnesses? Why did He not protect him against the disbelieving enemies of Uḥud who attacked him and caused him injury? Why did He not protect him against the Jewish woman who poisoned him? Or, why did Allāh not protect prophets before him from being killed or the Prophet Ayyūb (upon him peace) from the prolonged illness he suffered? The reality of course is that Allāh’s protection of His Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) refers to protection against his preaching being impeded and his functions of prophethood going unfulfilled – which would include protection from physical harm to some degree. But it does not preclude Allāh occasionally afflicting His prophets with trials at the hands of their enemies, for wisdoms known to Him. Ibn al-Qayyim thus writes of this very same argument against the ḥadīth:

“Just as Allāh (Glorified is He) protects them, preserves them, keeps them and befriends them, He tests them with whatever He wishes by the disbelievers persecuting them so they become entitled to His perfect honour, and so those after them from their nations and successors take solace when they are persecuted by people, so they see what occurred to the messengers and prophets, observe patience, show contentment and imitate them; and for the measure of the disbelievers to be filled so they are entitled to what has been prepared for them of immediate and future punishment…This is part of His (Exalted is He) wisdom in testing His prophets and His messengers via the persecution of their peoples.”[42]

This is taking Dr Akram Nadwi’s assertion at face value – that siḥr affecting the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) implies he was left unprotected by Allāh. But the reality is, of course, that Allāh did protect him from the prolonged effects of the siḥr by sending angels to inform him of it and of how to treat it. Noting this, Ibn Kathīr writes under the verse Dr Akram Nadwi cites (“Allāh protects you from people”): “The Jews schemed against him with siḥr and Allāh protected him from them and revealed the Mu‘awwidhatayan as treatment for the illness.”[43]

Siḥr did not Affect any of the Ṣaḥābah, Tābi‘īn?

Dr Akram Nadwi then argues:

Do you not know that the siḥr of the lying slanderers did not take effect in Abū Bakr, ‘Umar, ‘Uthmān, ‘Alī and nor the rest of the Ṣaḥābah and Tābi‘īn, nor Abū Ḥanīfah, al-Thawrī, al-Awzā‘ī, Mālik, Ibn ‘Uyaynah, Ḥammād ibn Zayd, al-Shāfi‘ī, Abū Thawr, Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal, al-Bukhārī, Muslim and those that followed them from the notable imāms? Then, you head towards this Prophet (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) who Allāh has supported with evident signs, shining proofs, clear demonstrations and irresistible powers, and accuse him of [being affected by] siḥr?! Do you not feel shame over slandering Allāh and His Messenger and inventing lies and spreading falsehoods?

Here, Dr Akram Nadwi makes a claim of absence, that none of the Ṣaḥābah and Tābi‘īn were affected by siḥr, nor any of the imāms that he named. How does he know this? Are all incidents of siḥr, or all illnesses, documented about all people affected by them? This is obviously pure rhetoric, completely lacking in any substance.

Nonetheless, it will be sufficient to find one incident of the Ṣaḥābah or Tābi‘īn being affected by siḥr to falsify this claim. We will show below that ‘Ā’ishah and Ḥafṣah (Allāh be pleased with them), mothers of the believers, were both affected by siḥr. This will serve to falsify Dr Akram Nadwi’s claim and also show that siḥr and being affected by it was not something unheard of in that era; while it may not have been something very pervasive, it was not something that was altogether non-existent as Dr Akram Nadwi would have us believe.

Siḥr on ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be Pleased with Her)

Imām Mālik narrates in his Muwaṭṭa’ from Abu ‘l-Rijāl Muḥammad ibn ‘Abd al-Raḥmān from the latter’s mother ‘Amrah that ‘Ā’ishah fell ill and was informed by a man from Sindh that she has been affected by siḥr; the man described to her the person who was responsible for the siḥr; ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her) recognised the individual, who was a slave of hers, and summoned her, and she confessed; ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her) then sold her to a group of people that treat their slaves badly; she was then informed in a vision of how to treat herself from the siḥr, and was cured.[44]

The same narration is found in Muṣannaf ‘Abd al-Razzāq from Sufyān ibn ‘Uyaynah narrating from Yaḥyā ibn Sa‘īd al-Anṣārī from Abu ‘l-Rijāl Muḥammad ibn ‘Abd al-Raḥmān.[45]

Ḥāfiz Ibn Ḥajar says of this narration: “Its chain is ṣaḥīḥ.”[46]

Siḥr on Ḥafṣah (Allāh be Pleased with Her)

Ibn Abī Shaybah narrates from ‘Abdah ibn Sulaymān from ‘Ubaydullāh ibn Umar from Nāfi‘ from Ibn ‘Umar (Allāh be pleased with him) that Ḥafṣah (Allāh be pleased with her) was affected by siḥr so she apprehended the sorcerer and had them executed.[47]

Imām Mālik also records the account in his Muwaṭṭa’ via Muḥammad ibn ‘Abd al-Raḥmān ibn Sa‘d ibn Zurārah who narrates it without citing his source.[48] Imām Mālik comments after narrating it:

“The sorcerer who performs siḥr without another having performed it for him, he is equivalent to the one Allāh has said of in His Book: ‘Certainly they know those who purchased it [i.e. siḥr] will have no share in the afterlife.’ Thus, I believe he is to be executed for that when he performs it himself.”[49]

If siḥr was not something real and had no effect on people in that era, why would Imām Mālik make such a comment?

Ibn Kathīr says in authenticating the above narration of Ḥafṣah: “It is ṣaḥīḥ that a slave-girl of Ḥafṣah, mother of believers, performed siḥr on her so she ordered her execution.”[50]

The above clearly falsifies Dr Akram Nadwi’s claim that none of the Ṣaḥābāh or Tābi‘īn were affected by siḥr. Will he retract and accept that this offhand comment of his was wrong? Furthermore, the second caliph, ‘Umar (Allāh be pleased with him), gave out an order to execute sorcerers; Bajālah ibn ‘Abdah of Baṣrah mentions that when this order came, they executed three sorcerers.[51] This shows there were others in that era that were affected by siḥr.

Wisdom in Being Affected by Siḥr

Moreover, apart from the general wisdom of suffering trials mentioned earlier, there is wisdom in the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) specifically being influenced by siḥr. In Kashf al-Asrār, an early (sixth century) work on Qur’ānic commentary, the author Rashīd al-Dīn al-Mayburī writes:

“If it is asked: What is the wisdom in siḥr penetrating and overcoming the Prophet (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) and why did Allāh not turn the plot of the plotter against him by nullifying his plot and siḥr? We say: The wisdom in it is to prove the veracity of Allāh’s Messenger (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) and the genuineness of his miracles and the falsehood of those who ascribe to him sorcery and soothsaying because the siḥr of a sorcerer took effect in him until some things became unclear to him and he suffered from [different] types of pain, and the Prophet (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) was not aware of that until he supplicated and supplicated and supplicated, and [only] then Allāh responded to him and made clear to him his affair. Had the miracles that appeared [on his hands] which ruptured the norms been from the category of siḥr as his enemies claimed, the siḥr that was done on him would not have been unclear to him and he would have had access to repelling it by himself; this, with praise to Allāh (Exalted is He), is from the strongest of proofs for his prophethood.”[52]

Why only ‘Ā’ishah?

Dr Akram Nadwi presents further reasons for rejecting the ḥadīth. He writes:

Had siḥr continued with the Prophet for six months as has come in some routes of the ḥadīth, the report would have spread amongst the specific and general Muslims, and extreme worry and nontrivial disturbance would overcome them, and they would expend all effort to treat and cure him. When sickness befell him, he would consult doctors. No one related this report – in spite of the motives for its widespread transmission – via a ṣaḥīḥ route except from ‘Ā’ishah, mother of believers, Allāh be pleased with her, and a report being isolated in a context that demands it being widespread is termed irregularity (shudhūdh).

He is trying to argue from this that the ḥadīth of ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her) is irregular or an anomaly (shādhdh), and thus should be disregarded. Dr Akram Nadwi does not provide any source for the principle he cites, nor what the “motives” for the widespread transmission of this narration to future generations would be.

Irregularity (shudhūdh) of the kind he refers to only arises when there is a widespread practice amongst the early generations and thus a need for any report opposing or prohibiting the practice to be widely narrated and known, and yet there is only one such narration.[53]

But here, how would a Muslim’s religious beliefs or practices be affected because of not knowing of this incident? In no way whatsoever. ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her) was a historian, biographer, teacher and narrator; hence, it makes sense that she would pass on this ḥadīth. Moreover, there is some evidence to suggest that the Prophet (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) was only affected in his intimacy with ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her) and not his other wives; and the narrations that mention “his wives” in general refer specifically to ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her); hence, it makes sense that she alone would narrate it.[54]

Moreover, the ḥadīth of ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her) clarifies that when the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) was asked why he did not bring the material out to the people (and publicly display the siḥr), he said he disliked for it to be a means of provoking people (and inciting them against each other).[55] This would in fact indicate the siḥr would not be widely reported and, contrary to Dr Akram Nadwi’s rationale, demonstrates that the context actually demanded that the issue remain relatively concealed.

Furthermore, it is not true that the report is found authentically only from ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her). It is also narrated by Zayd ibn Arqam (Allāh be pleased with him) from whom it is transmitted with an authentic chain according to Ḥāfiẓ al-‘Irāqī – as documented earlier.

Along the same lines, Dr Akram Nadwi goes on to mention that the narration is rendered more irregular by the fact that none of the other wives of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) reported it despite their love for him, and nor other Ṣaḥābah despite the illness being such that it wouldn’t be hidden to them. Dr Akram Nadwi makes a strange conflation between knowing something and narrating it! Or between something being shared amongst the Ṣaḥābah at the time the incident took place and narrating it afterwards to future generations.

To break it down: Just because it is not reported from them, it does not mean they did not report it; it might just be that the report from them did not reach us; and even if they did not report it, this does not mean they were not aware of it.

There are very good reasons why the kinds of “criticism” Dr Akram Nadwi offers here against this ḥadīth have never been offered by the scholars of ḥadīth to fault any ḥadīth. We can even venture to say that these criticisms are so obviously artificial to be not worthy of a serious response; and one wonders if Dr Akram Nadwi himself is really convinced of them or is simply presenting them disingenuously?

Strange Treatment

Dr Akram Nadwi offers a further contrived argument saying:

The method of his treatment from the effect of siḥr contains extreme strangeness and absurdity. His purification, prayer, recitation of Allāh’s book and his supplications did not help him, but rather what removed from him the effect of the siḥr of Labīd ibn A‘ṣam is from the kind that the sorcerers promulgate.

This again comes down to Dr Akram Nadwi’s Mu‘tazilī-esque materialism. Why does he not equally argue that the illnesses of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) that were treated by medication was not helped by his purification, prayer, recitation etc.? Furthermore, we know from this very narration that the Prophet’s supplications did help him! After supplicating persistently, angels came to him and informed him of what it was that had befallen him.

If Dr Akram Nadwi is arguing the method of treatment in the ḥadīth is “strange” because he is not familiar with how sīhr is treated, then this is his ignorance, and cannot be put forward as a legitimate argument against the ḥadīth.

Dr Akram Nadwi’s Mix-Up Theory

Dr Akram Nadwi then offers a theory of how the narration of ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her) came to be:

What I believe is that the incident is the incident of the Prophet’s (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) fever, and the issue became mixed up for one of the narrators below the mother of believers (Allāh be pleased with her). The incident of the fever is what Ibn ‘Abbās (Allāh be pleased with him) narrated saying: “Thursday, and what is Thursday! The Messenger of Allāh’s (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) pain became intense…” Similarly, ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her), mother of the believers, narrated the severity of his illness [at death].

I don’t think anyone who has even the faintest knowledge of ḥadīth believes that Dr Akram Nadwi is presenting this as a serious theory. The narrators “below ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with her)” are only Hishām and ‘Urwa. How could such imāms make such a preposterous error as to confuse fever for siḥr and then to add further completely unrelated details?

Ibn al-Qayyim quotes some misguided mutakallimīn who denied the ḥadīth of siḥr claiming Hishām got mixed up. He retorts:

“This – what these people say – is rejected according to the experts of knowledge because Hishām is from the most reliable and most learned of people; and none of the imāms have impugned him in such a manner that necessitates rejecting his ḥadīth…”[56]

There is no need here to further dwell on Dr Akram Nadwi’s theory. In fact, merely highlighting it here should be enough for most readers to see the lengths to which he will go to defend his stance – to a point of embarrassment and extreme irrationality.

Misquoting Ibn al-Qayyim

To prop up this evidently false theory of fever being confused for siḥr, Dr Akram Nadwi resorts to mistaken citation. He cites Ibn al-Qayyim in his talk on the topic in 2017 as follows:

In this narration of Hishām, somehow it became siḥr. This is one explanation and that actually is the explanation also Ibn al-Qayyim goes for. Ibn al-Qayyim said (raḥimahullāh):

السحر الذي اصابه صلى الله عليه وسلم كان مرضا من الأمراض

This was just an illness. It was not real magic.

To Dr Akram Nadwi’s credit, Ibn al-Qayyim did indeed write the above.[57] However, the disservice Dr Akram Nadwi has rendered his own case by plucking this statement out of Ibn al-Qayyim’s discussion – which actually affirms siḥr affected the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him), the very antithesis of what Dr Akram Nadwi is claiming – is quite phenomenal.

Ibn al-Qayyim is here merely pointing out that the siḥr performed on the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) resulted in no more than an illness, and there is no deficiency or blemish in this as illnesses are perfectly possible for prophets.[58] He is in no way supporting the thesis that Hishām ibn ‘Urwah or his father got mixed-up, something he directly refutes (as quoted from him above). He is in no way arguing that what is meant in the ḥadīth is not siḥr but an illness as Dr Akram Nadwi would have us believe; he is simply pointing out that the siḥr which caused a physical illness should not, in relation to the status of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him), be viewed as anything more than how we view other illnesses. Nowhere does he say the siḥr in question “was not real magic”.

This is apart from the fact that Ibn al-Qayyim thoroughly refutes some of the other arguments Dr Akram Nadwi made in the very book he cites and in the very section of the book from which he cites! Reading Ibn al-Qayyim’s full discussion in Badā’i‘ al-Fawā’id, as well as in his Zād al-Ma‘ād, should make it clear to any observer that Dr Akram Nadwi is here engaging in a classic case of citation bluffing.

Methodological Case

Providing a methodological framework to his rejection of the ḥadīth, Dr Akram Nadwi writes:

Did not those better than me by degrees reject ḥadīths in the Ṣaḥīḥs?…Did Abū Ḥanīfah and Mālik and their companions not reject the ḥadīth: “The two transacting partners have the option [to take back the agreement] for as long as they have not parted”? Did Abū Ḥanīfah and his companions not reject the ḥadīth of the animal whose milk is retained in the udders (muṣarrāh)? Did Mālik, al-Shāfi‘ī and Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal and their companions not reject the ḥadīth of the Prophet marrying while he was in the state of Iḥrām?

Dr Akram Nadwi here mentions three examples of imāms apparently not acting upon certain authentic ḥadīths. Later, he admits that these imāms have valid reasons for not acting upon them, but claims he too has equally valid reasons for rejecting the ḥadīth of siḥr. These “valid reasons”, however, are the very ones that have been analysed above, and one can see that they are far from being valid.

To demonstrate how the examples Dr Akram Nadwi cites does not in any way justify his rejection of the ḥadīth of siḥr we will briefly look at each of them in turn.

The first example is of a ḥadīth found in Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī and Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim stating: “The two transacting partners have the option [to take back the agreement] for as long as they have not parted.” Based on this ḥadīth, al-Shāfi‘ī and Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal opine that while the buyer and seller are still together after concluding a sale, they can each unilaterally revoke it before physically parting from one another. Abū Ḥanīfah and Mālik, however, opine that after both have agreed and concluded the sale, neither one can unilaterally revoke it even while they are still together. They interpret the ḥadīth to mean while the buyer and seller are negotiating the agreement, for as long as they have not parted on an agreement, each one can take back any offer that was made.

After quoting the ḥadīth, Imām Muḥammad states in his Muwaṭṭa’:

“We adopt this [ḥadīth]. Its explanation according to us according to what has reached us from Ibrāhīm al-Nakha‘ī is as he said: The transacting partners have the option as long as they do not part from the verbalisation of the sale. When the seller says: ‘I have sold to you’, he has the option of taking it back for as long as the other does not say: ‘I have bought’; and when the purchaser says: ‘I have bought for such-and-such’, he has the option of taking it back for as long as the seller does not say: ‘I have sold.’ This is the view of Abū Ḥanīfah and the generality of our jurists.”[59]

Ibn Khuwayz Mandād of the Mālikīs narrated the same interpretation from Imām Mālik.[60]

Hence, this is not an example of rejecting ḥadīth at all, but of offering a different interpretation. Does this in any way apply to the case at hand? Does Dr Akram Nadwi have an alternative interpretation to the ḥadīth of siḥr? It is obvious that in the case of the ḥadīth of siḥr, it is not possible to interpret it in any way apart from its plain meaning.

The ḥadīth of the animal whose milk is retained in the udders (muṣarrāh) refers to a ḥadīth also found in Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī and Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, stating: “Do not retain milk in the udders of camels and goats/sheep; whoever purchases it after [this] will be given the option between two decisions after having milked it: if he wants he can keep it and if he wants he can return it together with a ṣā‘ of dates.” It is not true that the “companions of Abū Hanīfah” did not act on this ḥadīth. Imam Abū Yūsuf, amongst the senior companions of Imām Abū Hanīfah, did act on this ḥadīth.[61] Imām Abū Hanīfah believed the ḥadīth to be abrogated by later ḥadīths,[62] and Imām al-Ṭaḥāwī explains at length which ḥadīths abrogated this earlier rule.[63] Thus, Abū Hanīfah does not reject that the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) taught what is found in this ḥadīth, but feels that it was not the final teaching, and hence is not to be implemented. Does this apply to the case at hand? Of course, when it comes to whether an event occurred or not, one cannot invoke the principle of abrogation.

The ḥadīth of marrying in the state of Iḥrām refers to a narration also found in Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī and Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim in which Ibn ‘Abbās (Allāh be pleased with him) reports that the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) married Maymūnah (Allāh be pleased with her) while he was in the state of Iḥrām. Imām Mālik, Imām al-Shāfi‘ī and Imām Aḥmad, however, opine that it is not allowed for one in Iḥrām to marry. Here, there are conflicting narrations. Some narrations mention that Maymūnah (Allāh be pleased with her) married the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) while he was not in Iḥrām. Of course, these two accounts cannot both be true at the same time, so those who subscribe to the view that it is impermissible to marry in Iḥrām consider the narration of Ibn ‘Abbās to be an error on Ibn ‘Abbās’s part; since he was only a child when the marriage occurred he could easily be mistaken, while those who narrated that the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) was not in Iḥrām were older and directly connected to the event i.e. Maymūnah (Allāh be pleased with her) herself and one acting as an intermediary between her and the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him).[64]

Does this apply to the ḥadīth at hand? Are there any conflicting narrations which show the Prophet was not influenced by siḥr in the manner that ‘Ā’ishah and Zayd ibn Arqam (Allāh be pleased with them) described?

What the above demonstrates is that the imāms Dr Akram Nadwi invokes did not summarily dismiss ḥadīth because it did not sit right with them; but provided a genuine and truthful analysis of the ḥadīths in question based on which they drew their conclusions. Dr Akram Nadwi uses this practice of the imāms to justify the contrived case he has manufactured against one of the most well-attested of ḥadīths!

Precedent & the Ḥanafī School

When presenting precedent for his view, Dr Akram Nadwi quotes only one premodern scholar: Abū Bakr al-Jaṣṣāṣ al-Rāzī (305 – 370 H). Abū Bakr al-Rāzī, however, was a Mu‘tazilī or at least heavily influenced by the Mu‘tazilah.[65] Abū Bakr al-Jaṣṣāṣ apparently also realised that his stance is against the madhhab of Fiqh he subscribed to (i.e. the Ḥanafī madhhab), since he transmits from Muḥammad ibn Shujā‘ al-Thaljī that Abu ‘Alī al-Rāzī asked Imām Abū Yūsuf, after the latter reported from Imām Abū Ḥanīfah that a sorcerer is to be executed, what a sorcerer (sāḥir) is. Abū Yūsuf replied:

“One from whom actions are discovered that are similar to what the Jews did to the Prophet (upon him blessing and peace), and according to what is transmitted in reports, when he achieves killing thereby; if he does not achieve killing thereby, he will not be executed because Labīd ibn al-A‘ṣam did siḥr on the Messenger of Allāh (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) but he did not execute him because he did not achieve killing thereby.”[66]

This clearly goes against Jaṣṣāṣ’s assertion that these narrations are false.[67] Nonetheless, Jaṣṣāṣ tries to justify the statement of Imām Abū Yūsuf in light of his Mu‘tazilī perspective by proposing that Imām Abū Yūsuf did not deny there was physical contact (mumāssah) in the siḥr of Labīd, and this may be referring to something like poisoning.[68] This is of course pure speculation and derives from his materialist outlook.

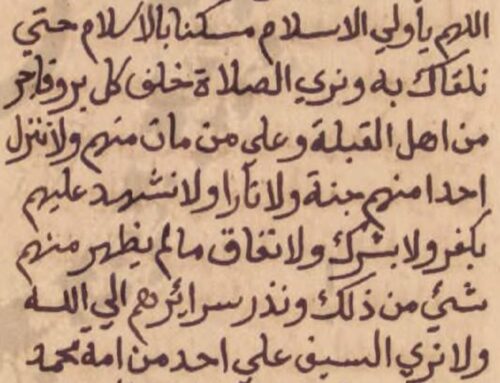

Imām Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan al-Shaybānī transmitted in his Muwaṭṭa’ the narration documented earlier that ‘Ā’ishah (Allāh be pleased with him) fell ill on account of siḥr. It was also mentioned earlier that Imām al-Ṭaḥāwī argued for the effects of siḥr from the ḥadīths of siḥr, of both ‘Ā’isha and Zayd ibn Arqam (Allāh be pleased with them). Thus, Jaṣṣāṣ’s view is obviously not representative of the Ḥanafī school that he subscribed to.

Dr Akram Nadwi is thus citing an anomalous, isolated opinion of someone known to be a Mu‘tazilī or be heavily influenced by Mu‘tazilī thought. In the pursuit of defending his controversial views, it seems for Dr Akram Nadwi it is permitted to quote even such a lone figure.

Siḥr of the Mind?

Dr Akram Nadwi also quotes the modernist Muḥammad ‘Abduh who says this ḥadīth does impugn the mental integrity of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) because it says he imagined things that did not occur. But as the scholars of the past have said, just because the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him), while under the influence of siḥr, would imagine or see things that were not real, it does not mean he believed them to be true; it is just like someone imagines or sees things in his sleep – it does not mean he believes those things actually occurred.[69] In fact, the Qur’ān records that Mūsā (upon him peace) was affected by siḥr to the point that he imagined the sticks of the sorcerers were running.[70]

Conclusion

From the above case study, the dangers inherent in a modernist approach to Islāmic teachings become evident. From an intellectual standpoint, we have seen in the case at hand that Dr Akram Nadwi has no academic legs to stand on, while the traditional and orthodox stance of Ahl al-Sunnah wa ‘l-Jamā‘ah is academically sound and has no valid objections. Dr Akram Nadwi’s apparent commitment to certain modernist ideas has led him to be irrational and offer some senseless and absurd arguments. Surely such blind, irrational dogmatism is not healthy.

From a religious standpoint, departing from traditional, orthodox positions based on modernist inclinations has the potential of causing one to adopt positions far worse than the one critiqued here; it has the potential of leading one to reject fundamental Islāmic beliefs, and as a consequence, losing Islām altogether.

Muḥammad ibn Sīrīn (Allāh have mercy on him) famously said, “This knowledge is religion so consider who you take your religion from.”[71] True knowledge is the knowledge of the Ṣaḥābah, Tābi‘īn and the imāms of this Ummah. Modernist “intellectuals”, like Dr Akram Nadwi, who attempt to overturn teachings that have been passed down unquestioningly and uninterruptedly amongst the scholars of the Ummah are the very kinds of people Muḥammad ibn Sīrīn has warned against.

For those who take their religion seriously, and worry for their next life, is it really worth taking the risk of acquiring knowledge from someone like Dr Akram Nadwi who has demonstrated he has no interest in preserving traditional orthodoxy, and at least in the case at hand has incessantly attacked traditional orthodoxy while doggedly and desperately supporting an indefensible anti-traditional modernist perspective?

[1] Tafsīr al-Ṭabarī, Maktabah Ibn Taymiyyah, 2:438

[2] Muṣannaf Ibn Abī Shaybah, Shirkah Dār al-Qiblah, 12:63-4

[3] Badā’i‘ al-Fawā’id, Dār ‘Ālam al-Fawā’id, p.739-40

[4] Al-Shifā, Jā’iza Dubai, p. 719

[5] Copied in the appendix here: https://www.basair.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/الرد-على-الاستاذ-أكرم-الندوي-في-انكاره-لحادثة-السحر.pdf

[6] It is not the purpose of this refutation to be exhaustive, but to highlight the important points from his Arabic article and present why they are fallacious

[7] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, 3175, 3268, 5763, 5765, 5766, 6391; Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, 5697, 5698

[8] Tadrīb al-Rāwī, Dār Ibn al-Jawzī, 1:134, 147

[9] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, 5765; Musnad al-Ḥumaydī, 261

[10] Al-Umm, Dār al-Wafā’, 2:565

[11] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, 3268

[12] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, 6391

[13] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, 5763

[14] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, 3175

[15] Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, 5697

[16] Musnad Aḥmad, 24347

[17] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, 5766; Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, 5698

[18] Musnad Aḥmad, 24650

[19] Sharḥ Mushkil al-Āthār, 5934

[20] Imām al-Bukhārī also mentions the Madīnan scholar, ‘Abd al-Raḥmān ibn Abi ‘l-Zinād (d. 174 H), in the list of those who narrate this ḥadīth from Hishām ibn ‘Urwah. (Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, 5763)

[21] It is worth noting here that Imām Bukhārī cites the ḥadīth no less than six times in his Ṣaḥīḥ.Bukhārī’s finesse in carefully selecting and organising ḥadīths in his Ṣaḥīḥ is not something unfamiliar to Dr Akram Nadwi. In one of his lessons, he says: “How much he [i.e., Bukhārī] does, you really cannot imagine. Even if he brings one ḥadīth seven times, so which isnād bring first time, which one second time, which one third time: even that he decides. It is not that, you know, these seven aḥādīth, so seven times randomly. No! Every time he makes intention why he includes that time. Try to understand this thing, what he does really. Amazing person.” In light of this, the pressing question for Dr Akram Nadwi is what could possibly have driven Imām al-Bukhārī to cite this ḥadīth six times in his Ṣaḥīḥ? What was Bukhārī’s intention with each citation of a report which Dr Akram Nadwi considers nothing short of calumnious and fabricated?

[22] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, 5765

[23] Fatḥ al-Bārī, Dār Ṭaybah, 13:205

[24] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, 3175

[25] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, 3268

[26] Muṣannaf ‘Abd al-Razzāq, 20673; see also: Tafsīr al-Ṭabarī, Hajr, 2:351

[27] Muṣannaf Ibn Abī Shaybah, no. 23984; 12:62

[28] Musnad Aḥmad, 19267

[29] Itḥāf al-Sādat al-Muttaqīn, 7:136

[30] Sharḥ Mushkil al-Athār, 15:181

[31] Ibid. 15:180

[32] Ta’wīl Mukhtalif al-Ḥadīth, p. 262-5

[33] Qur’ān, 2:87, 91, 3:21, 3:112, 3:181, 3:183, 4:155, 5:70

[34] Qur’ān, 38:41

[35] Rūḥ al-Ma‘ānī, Mu’assasat al-Risālah, 23:303

[36] A‘lām al-Ḥadīth, p. 1500-1

[37] Al-Mu‘lim, 3:159

[38] Iḥyā’ ‘Ulūm al-Dīn, Dār al-Minhāj, 1:111

[39] Lit: one affected by siḥr

[40] Tafsir al-Razi, Dār al-Fikr, 30:188

[41] Ghāyat al-Amānī fī Tafsīr al-Kalām al-Rabbānī, Dār al-Ḥaḍarah, 7:1359

[42] Badā’i‘ al-Fawā’id, p. 745

[43] Tafsīr Ibn Kathīr, Maktabah Awlād al-Shaykh, 5:291

[44] Muwaṭṭa’ of Abū Muṣ‘ab al-Zuhrī, 2782; of Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan al-Shaybānī, 843; Muṣannaf ‘Abd al-Razzāq, 19797.

[45] Muṣannaf ‘Abd al-Razzāq, 19798

[46] Talkhīṣ al-Ḥabīr, Mu’assasah Qurṭubah, 4:77

[47] Muṣannaf Ibn Abī Shaybah, 28491

[48] Muwaṭṭa’ of Yaḥyā ibn Yaḥyā al-Laythī, 2553

[49] Ibid. 2554

[50] Tafsīr Ibn Kathīr, Maktabah Awlād al-Shaykh, 1:538

[51] Al-Umm, Dār al-Wafā’, 2:566

[52] Kashf al-Asrār wa ‘Uddat al-Abrār, p. 3187-8

[53] Dirāsāt fī Uṣūl al-Ḥadīth ‘alā Manhaj al-Ḥanafiyyah, p. 303-317

[54] Kashf al-Asrār wa ‘Uddat al-Abrār, p. 3188

[55] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, 3268, 5763; Badā’i‘ al-Fawā’id, p. 739

[56] Badā’i‘ al-Fawaid, p. 740

[57] Badā’i‘ al-Fawā’id, p.742.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Muwaṭṭa’ Muḥammad, 785

[60] Fatḥ al-Bārī, 5:568

[61] Sharḥ Ma‘ānī al-Āthār, 4:19

[62] Ibid.

[63] Ibid. 4:19-22

[64] Al-Mughnī, Dār ‘Ālam al-Kutub, 5:164

[65] Nāẓūrat al-Ḥaqq, Dār al-Fatḥ, p. 208-10

[66] Aḥkām al-Qur’ān, Dār Iḥyā al-Turāth al-‘Arabī, 1:62

[67] Aḥkām al-Qur’ān, 1:60

[68] Aḥkām al-Qur’ān, 1:62

[69] Al-Mu‘lim, 3:159; Ikmāl al-Mu‘lim, 7:87-8; Fatḥ al-Bārī, 13:206-7

[70] Qur’ān 20:66

[71] Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, 26

Jazakallah. Explained very well.