By Mufti Zameelur Rahman

Introduction

Asrar Rashid of Birmingham, UK, is a preacher who claims to be non-partisan, non-sectarian, and an objective, unbiased “Sunnī Muslim”. However, the subjectivity, and often baselessness, of his claims on the nature and roots of one of the most pronounced intra-Sunnī divides in the Indian Subcontinent proves otherwise. His entire thesis on the causes of the divide is coloured by highly subjective, sometimes evidently false, sectarian readings of history.

In the following, we will deconstruct his historical narrative from a recent talk[1] which has been uploaded online. Relevant parts of the talk will be transcribed and responded to in some detail. Asrar Rashid provides his account in a roughly chronological order. Thus, the following will document (and transcribe) the substantive points in his account and demonstrate the clear bias, subjectivity, lack of academic rigour, and at times outright falsity, of his claims, exposing the fact that they are tainted by sectarian allegiances and tropes, and are not based on an objective assessment of the evidence. In the course of the response, we also hope readers will gain a better appreciation of some of the oft-discussed issues that Asrar Rashid touches upon.

Sectarian bias will often cloud a person’s judgement. If, for example, sectarian mythology is rooted in the idea that Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd wrote Taqwiyat al-Īmān after having come under the direct influence of Arabian Wahhābīs, it will be difficult to entertain the possibility (in this case, the fact) that Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd wrote Taqwiyat al-Īmān years before setting foot in the Ḥijāz, that is, before even the remotest contact with the Arabian Wahhābīs. In deconstructing Asrar Rashid’s narrative, we will observe several other such examples of conclusions that are clearly products of a biased reading.

In constructing this biased narrative, Asrar Rashid also resorts to some clearly false claims, like the claim that ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī was hung by the British (while in reality he died a natural death at the Andaman Islands), or that Nuzhat al-Khawāṭir reports that ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī only revolted against the British because they stopped paying him (whereas nothing of the sort is mentioned in Nuzhat al-Khawāṭir).

In short, the response will challenge Asrar Rashid’s claims to objectivity. If he really is objective and sincere, as he claims, will he reassess the claims he has made, some of which are patently false, in light of the evidence that will be cited below? Will he answer the challenges that will be put to him below in an objective manner? Or will he regurgitate the standard claims and dismiss the evidence in favour of sectarian (mis)readings of history (and thus proving he is only shedding the label of sectarianism and not its reality)?

Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd and Taqwiyat al-Īmān

Asrar Rashid says:

Then in the 1800s, two additional influential books were written. One by Charles Darwin in 1859… Additional to this, a book was written by an individual known as Ismā‘īl al-Dehlawī. The book was entitled Taqwiyat al-Īmān. This book was released in 1821. I would say these are the two most notorious books written in the 1800s.

Mawlānā Nūr al-Ḥasan Kāndhlawī has written a thorough study on Taqwiyat al-Īmān.[2] Most of the discussion on Taqwiyat al-Īmān below will, therefore, be based on his research.

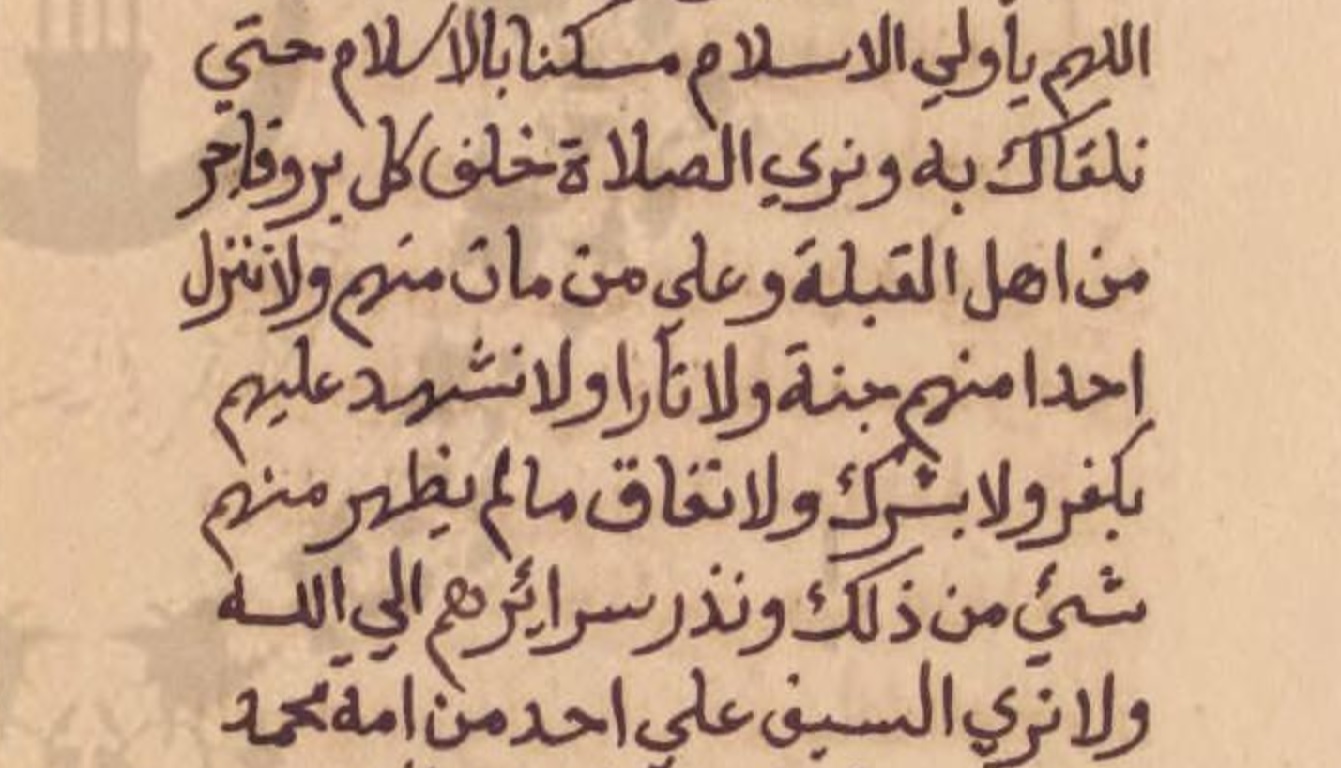

Taqwiyat al-Īmān was written some time in, or before, the year 1818.[3] We know this because the oldest available manuscript dates to 1818, preserved in Madrasa Ṣawlatiyya at Makkah.[4] Taqwiyat al-Īmān was first published (i.e. printed) in 1826 or 1827 at the Maṭba‘ah Aḥmadī run by Sayyid ‘Abdullāh ibn Sayyid Bahādur ‘Alī.[5] Maṭba‘ah Aḥmadī was also the first to publish al-Fawz al-Kabīr by Shāh Waliyyullāh, Mūḍiḥ al-Qurān by Shāh ‘Abd al-Qādir and other works of the Waliyyullāh family.[6] Asrar Rashid should therefore identify his source for the claim that Taqwiyat al-Īmān was first released in 1821.

It appears the claim, not surprisingly, may be the product of sectarian narrative bias, according to which, Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd (1779 – 1831) came under the influence of Wahhābī preachers when he visited the Ḥijāz, and Taqwiyat al-Īmān was a product of direct Wahhābī influence. More about this “contact theory” will be mentioned later. Since Shāh Ismā‘īl left for Ḥajj in 1821, it appears the claim is being made that Taqwiyat al-Īmān was released in the same year. But there are several problems with this theory. Firstly, there is clear evidence that Taqwiyat al-Īmān was written at the latest in 1818, several years before the Ḥajj. Secondly, Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd arrived at Ḥijāz in 1822, not 1821.[7] Thirdly, Taqwiyat al-Īmān is based on an earlier work of Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd in Arabic, called Radd al-Ishrāk, which was one of his earliest works written around the year 1798.[8]

In brief, Taqwiyat al-Īmān was written several years before the Ḥajj journey of 1821 (and was first published some years after the Ḥajj journey). If Asrar Rashid is objective, will he concede the point that Taqwiyat al-Īmān was written before the Ḥajj journey, before the remotest contact with the Arabian Wahhābīs?

Did the British Royal Asiatic Society Print and Distribute Taqwiyat al-Īmān?

On the subject of Taqwiyat al-Īmān, Asrar Rashid mentions in a related talk[9]:

He wrote a work that is known as Taqwiyat al-Īmān in 1821…Of course the book was published by the Royal Asiatic Society. So the British published the work, they disseminated the work in Urdu and English, in the Indian subcontinent. These are the facts that they dislike me mentioning. These are the points. These are facts. Today I would like to say people are not living in villages. These Muslims in UK are not living in villages, where anyone is able to misinform them. Go and check these facts for yourselves. Most of these books are available as PDFs on the internet.

The “fact” Asrar Rashid refers to is a myth that was created some time during the latter half of the twentieth century. Refuting this myth, Mawlānā Nūr al-Ḥasan Kāndhlawī mentions: “Taqwiyat al-Īmān was never published by the Asiatic Society, neither before its publication at Maṭba‘ Aḥmadī nor after. I have a copy of an old index of the Asiatic Society’s publications printed in January 1833. The index lists all the Arabic, Persian and Urdu publications of Asiatic Society up to that date, but there is no sign of Taqwiyat al-Īmān there. Furthermore, the available books printed by the Asiatic Society, and its published articles, that I have seen do not include Taqwiyat al-Īmān.”[10] Mawlānā Nūr al-Ḥasan shows that the claim that the British published and distributed Taqwiyat al-Īmān comes about a century and a half after the events.

He mentions that the only truth to this allegation is that the Royal Asiatic Society published an article by Mir Shahamat Ali that included an English translation of Taqwiyat al-Īmān. This was published as part of their journal, most likely some time in the 1850s.

If Asrar Rashid is objective, will he accept that there is no reliable evidence for his claim that the British printed an Urdu edition of Taqwiyat al-Īmān and distributed it in India?

Shāh Ismā‘īl’s Alleged Links with the Arabian Wahhābīs

Asrar Rashid further says:

The book that led to the inception of sectarianism within the Indian subcontinent, as well as the book that led to a further division…The division caused by the work of Muḥammad bin ‘Abd al-Wahhāb as well as the work of Ismā‘īl al-Dehlawī was a real theological issue that faced the Muslims in the Middle East as well as the Indian subcontinent. How were the two issues linked? Ismā‘īl al-Dehlawī was born in 1879 (sic)[11]. Muḥammad bin ‘Abd al-Wahhāb was still alive. And Muḥammad bin ‘Abd al-Wahhāb was very influential in the Arabian peninsula at that time. When Muḥammad bin ‘Abd al-Wahhāb died, passed away, in 1892 (sic)[12], Ismā‘īl al-Dehlawī was 13 years old. One of the places that Ismā‘īl al-Dehlawī travelled to was the Arabian peninsula and he adopted what people termed at that time as the “Wahhabi creed”.

Asrar Rashid also claims that Shāh Ismā‘īl’s uncles and forefathers were “Sunnīs”, but that “he was against the methodology of his forefathers”.

Both the claims that Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd came under direct influence of the Arabian Wahhābīs and that he was against the methodology of his forefathers are completely baseless.

The alleged links with the Arabian Wahhābīs suffer from the following problems.

Firstly, as stated, there is no evidence. Harlan O. Pearson a (neutral) academic researcher on Sayyid Aḥmad Shahīd’s movement states while discussing Shāh Ismā‘īl and the group’s pilgrimage:

The Indian Muhammadi [i.e. the movement of Sayyid Aḥmad Shahīd and Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd] had no apparent connection with the Arabian Wahhabi movement. By performing the pilgrimage, they were performing a basic religious duty in preparation for their later activities.[13]

Secondly, when Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd, together with a large cohort, arrived at Arabia, Wahhābīs had already been defeated and had been expelled from the Ḥijāz, and thus held no influence there. Mawlānā Ḥusayn Aḥmad Madanī explains:

It becomes very clear from the abovementioned events that Ḥaḍrat Sayyid [Aḥmad Shahīd] Ṣāḥib and his companions arrived at Makkah Mu‘aẓẓamah at the end of 1237 H (1822 CE)…This is a period in which no remnant or trace remained of the Wahhābī government and its peoples neither in Ḥijāz nor any town or village of Najd.

In fact, five years previously Egyptian forces under the command of Ibrāhīm Pāshā ibn Muḥammad ‘Alī Pāshā, the viceroy (Khedive) of Egypt, under instructions from Sulṭān ‘Abd al-Majīd Khān, crushed them, not only in Madīnah Munawwarah and Makkah Mu‘aẓẓamah, but in the whole of the Ḥijāz and the famous areas of Najd. Those that were left of them became absconders, fleeing to far off places in mountains and jungles. Thus, Shāmī has mentioned them clearly in the Ḥāshiyah of al-Durr al-Mukhtār, in the third volume, stating that in 1233 H, Egyptian forces completely annihilated them.

On page 87 [of The Indian Musalmans] W.W. Hunter, after mentioning that the Wahhābīs took control of Makkah Mu‘aẓẓamah, Madīnah Munawwarah and other regions, wrote: ‘It was Mehmet Ali, Pasha of Egypt, who at last succeeded in crushing the Reformation. In 1812, Thomas Keith, a Scotchman, under the Pasha’s son, took Medina by storm. Mecca fell in 1813; and five years later, this vast power, which had so miraculously sprung up, as miraculously vanished, like a shifting sand mountain of a desert.’ …

In short, when Sayyid Ṣāḥib and his companions reached Makkah Mu‘aẓẓamah in Sha‘bān of 1237 H, no Wahhābī ruler, scholar or preacher was there, and nor were they at the borders or fringes. Muḥammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhāb’s death had occurred long before. Thus, they had no chance of adopting the Wahhābī methodology from them, and nor is it established through any reliable means that they had met with any Wahhābī.

Thus, to affiliate these respected ones to this sect is a completely slanderous and false propaganda. These respected ones were disciples of Ḥaḍrat Shāh ‘Abd al-‘Azīz Ṣāḥib Dehlawī (Allāh’s mercy be upon him), and are his followers in external and esoteric knowledge. They had received such perfection from the benefit they acquired [from him] that no match or equal of theirs could be found in depth of knowledge, juristic understanding, Taṣawwuf, speech and writing, neither in Hindustan nor in Arabia, Egypt, Levant and so on. Their writings, speeches and actions are a testament to this. How can such people of perfection become followers and imitators of others? How can this come to a sound mind? Especially when these others are less than them in every perfection?[14]

Would Asrar Rashid accept that there is no objective historical evidence to support his “contact theory”?

Detailed accounts are available of the Ḥajj journey[15], including that Shāh Ismā‘īl taught Ḥujjatullāh al-Bālighah (the celebrated work of his grandfather) while at the Ḥijāz, that the Ṣūfī tract Ṣirāṭ e Mustaqīm was translated to Arabic, and that many pledged their allegiance to Sayyid Aḥmad Shahīd (1786 – 1831), and so on, but nothing about coming into contact with Wahhābī preachers.

Thirdly, as explained earlier, Asrar Rashid believes Taqwiyat al-Īmān was written after his conversion to Wahhābī belief. But as explained earlier, a simple chronology disproves this. Radd al-Ishrāk and its derivative work, Taqwiyat al-Īmān, were both written years before the Ḥajj.

Differences between Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd and Wahhābīs

Fourthly, there are important differences between the ideologies of Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd and the Wahhābīs. In Taqwiyat al-Īmān, which was supposedly written under Wahhābī influence, Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd wrote: “Yes, if ‘O Allāh give me something by means of Shaykh ‘Abd al-Qādir’ is said, that is fine.”[16] In other words, he permits Tawassul through personalities, which Wahhābīs do not.

In another work written in Arabic called ‘Abaqāt[17], on the topic of Ṣufī metaphysics, Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd includes the Ash‘arīs and Māturīdīs amongst those on the truth, as well as those who subscribe to the different Ṭarīqas of the Ṣūfīs.

He states:

Divergence and disagreement have occurred in every field. It is of two kinds. One is divergence between those on falsehood and those on truth, like the divergence between jurists of the Shī‘ah and of Ahl al-Sunnah; and between Ash‘arīs and Mu‘tazilah; or between the heretical Wujūdīs and the learned Wujūdīs; or between those who use wine and intoxicants in their meditations and those who use litanies and prayer; or between those who treat the vanity of the heart by abandoning the main features of Sharī‘ah and those who treat it by giving attention towards sins and falling short in good deeds. You can find similar examples. The rule on such divergence is the necessity of calling one group specifically correct and, in the same way, calling the other incorrect.

Another kind of divergence is amongst adherents of truth (ahl al-ḥaqq) like the divergence between the four imāms or between the Ash‘arīs and Māturīdīs or between the Warā’i Wujūdīs and the Ẓilli Shuhūdīs, or between the adherents of the different Ṭarīqas (of Taṣawwuf). The rule on this is that each of them are on a right road in most issues, and each have a direction to which they turn, so compete with each other in good deeds [and don’t argue with each other]. Whoever follows any one of them will succeed in attaining the goal.[18]

Thus, Shāh Ismā‘īl explicitly states his allegiance to Sunnī schools of ‘aqīdah, in contrast to Wahhābīs. Will Asrar Rashid acknowledge this?

It is not certain when ‘Abaqāt was written. In a later work called Yak Rozah (written in 1826), when constructing his arguments against ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī, Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd references the beliefs of the Ash‘arīs and Māturīdīs, in particular their differences on the topic of “Takwīn”.[19] This demonstrates that even after his Ḥajj journey, he did not abandon his affiliation to these two schools. Will Asrar Rashid accept that this would be uncharacteristic of a true “Wahhābī”?

There is no evidence therefore that Shāh Ismā‘īl abandoned the methodology of his forefathers. In ‘Abaqāt, he declares that his major source of learning is from his uncles,[20] and the work ‘Abaqāt derives from the teachings of his grandfather.[21] Ṣiddīq Ḥasan Khān (1832 – 1890) writes about Shāh Ismā‘īl: “He followed the footsteps of his grandfather in word and deed both, and completed what his grandfather started, and fulfilled what was obligatory on him, and what is for him remains…He wasn’t one to invent a new methodology in Islām as the ignorant claim.”[22]

Some may assume that Shāh Ismā‘īl’s emphasis on eradicating idolatrous practices suggests foreign influence. But, in fact, even such teaching can be traced to the writings of Shāh Waliyyullāh.[23] Moreover, Shāh Ismā‘īl’s conception of shirk is not the same as Wahhābīs, more on which will be written below.

“The Wahhābī Creed”

Asrar Rashid continues:

The Wahhābī creed at that time, and in later times also, the main creedal points in which they had heresy was one being anthropomorphism as well as believing that the Messenger of Allāh (ṣallallāhu ‘alayhi wasallam) has no connection with his nation today…This belief was a belief that the Messenger of Allah (ṣallallāhu ‘alayhi wasallam) is connected to his nation. But the movement of Muḥammad bin ‘Abdil Wahhāb removed this from some people in the Middle East and the movement of Ismā‘īl al-Dehlawī removed this from some of the people of the Indian subcontinent.

Asrar Rashid identifies two areas of “Wahhābī heresy”, one anthropomorphism and the other removing a connection with the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him). Some have alleged that Shāh Ismā‘īl promoted anthropomorphism, but this is an unsubstantiated claim[24] and contradicts his explicit statements found in ‘Abaqāt. [25]

Moreover, Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd did not remove any connection with the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him). He wrote a eulogy of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) called Mathnawī Silk-e-Nūr. Part of the eulogy states: “Although outwardly that pure body is hidden from these eyes beneath the earth,

still, its light stands in its place, as there is a place for it in every sound heart.”[26]

Moreover, as Mawlānā Madanī states:

In Wahhābī belief and practice, it is impermissible to travel with the objective of visiting the revered Messenger of Allāh (Allāh bless him and grant him peace). Thus, their writings and works are available [stating this]. If, Allāḥ forbid, this was the belief of these respected ones [i.e. Sayyid Aḥmad Shahīd, Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd and their followers], why did the entire group, having travelled to Makkah Mu‘aẓẓamah, go to Madīnah Munawwarah? And why did they remain there for three months, from the end of Dhu l-Ḥijjah until Rabī‘ al-Awwal?[27]

Thus, the idea that Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd removed the Prophet’s (peace and blessings be upon him) connection with the Ummah is unfounded.

Shāh Ismā‘īl and Shirk

Strangely, Asrar Rashid omitted to mention Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd’s alleged adoption of flawed Wahhābī conceptions of shirk. In Wahhābī belief, certain actions like slaughtering an animal while taking an individual’s name or calling out for help from a dead saint are deemed to be major shirk that expel a person from Islām, irrespective of the person’s intentions or beliefs. [28] The difference between Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd and Wahhābīs on this point will be explained in a little more detail, as in the mind of many of Shāh Ismā‘īl’s detractors this is the clearest evidence of a connection between his ideology and that of Wahhābīs.

While Shāh Ismā‘īl condemns idolatrous practices, the people he targets are those who believe saints have extraordinary powers in which, like Allāh, they operate above created means (asbāb) and are free-acting. He describes the kind of shirk he is addressing in Radd al-Ishrāk, from which Taqwiyat al-Īmān derives.

He states in Radd al-Ishrāk:

Realise that the shirk which the divine books came to nullify and the prophets were sent to eradicate is not limited to someone believing that the one he worships is equal to the Creator (Blessed and Exalted is He) in the necessity of existence or in encompassing knowledge of all creation or in creating the basic existents like the heaven and the earth, because it is not from the character of a human being to be mixed up with such belief unless he is disfigured like Fir‘awn and his likes, and no one can believe that the divine books were revealed and prophets were sent only to correct such disfigured ones only. How can this be when the Arab idolaters who the Prophet (Allāh bless him and grant him peace) called “idolaters” and fought and spilt their blood, put their children into captivity, and took their wealth as spoils, would not believe this as evidenced by His (Exalted is He) statement: “Say: In Whose hand is the dominion of all things and He grants protection and is not granted protection against, if you know, and they will say: Allāh. Say: Then how are you deluded?’ (Qur’ān, 23:88-9) and there are many such verses?

Rather, the meaning is to make another besides Allāh a partner with Him (Exalted is He) in divinity (ulūhiyyah) or lordship (rubūbiyyah). The meaning of “divinity” is to believe in respect to him that he has reached such a degree in qualities of perfection like encompassing knowledge, control by mere power and will, that he is beyond comparison and similarity with the rest of creation; which is by believing that nothing occurs…but that it is impossible for it to be hidden from his knowledge and he is witness to it; or believing that he controls things by force, meaning his control is not part of the means [Allāh has put in creation] but he has control over the means. The meaning of “lordship” is that he has reached such a degree in referring needs [to him], asking for solutions to problems and asking for the removal of tribulations by his mere will and power over the means that he deserves utmost servility and humbleness. That is, there is no limit to the extent of servility and humbleness shown to him, and there is no servility or humbleness but it is good in respect to him, and he is deserving of it…[29]

Shāh Ismā‘īl goes onto mention some actions which are derived from these beliefs. Shirk, in his understanding, is fundamentally a mistaken belief, not something based merely on a person’s actions. Actions, however, can be manifestations of shirk, but these do not necessarily take a person out of Islām. ‘Uthmān Nābulūsī, a student of Sa‘īd Fūda in Jordan, and author of a work refuting mistaken Wahhābī conceptions on “Tawḥīd”, commented after reading Shāh Ismā‘il’s introduction to the above work (Radd al-Ishrāk): “This introduction is completely unproblematic, and there is a massive difference between what he said and what Muḥammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhāb said.”[30]

The shirk that Shāh Ismā‘īl is refuting is similar to what Shāh Waliyyullāh described as the belief of the idolaters, that is, a belief in Allāh being in need of subordinate deities who function as His agents in controlling certain affairs.[31] Towards the beginning of Taqwiyat al-Īmān itself, Shāh Ismā‘īl explains that this is the shirk he is refuting. While describing the people he is refuting, he states:

If a sensible person were to ask these people, “You claim īmān but do acts of shirk. Why do you combine these two [contradictory] paths?” They answer: “We do not do shirk but we are expressing our devotion towards prophets and saints. We would only be idolaters (mushrik) if we regarded these prophets, saints, pīrs and martyrs as equals to Allāh. This is not what we believe. Rather, we regard them to be slaves of Allāh and His creatures. Their power of discretion was given to them by Allāh Himself. By His approval they apply their control over the universe. Calling onto them is the same as calling onto Allāh, asking help from them is the very same as asking Him. They are beloved to Allāh, so whatever they want they will do. They will intercede to Him on our behalf and are His agents. By reaching them we reach Him and by calling them we draw near to Allāh. The more we obey them the closer we get to Allāh.”[32]

As can be seen, Shāh Ismā‘īl is addressing a specific type of belief amongst some of the ignorant Muslims of India, which amounts to major shirk, and is akin to the idolatrous beliefs of the pagan Arabs the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) fought. In his condemnation of shirk, Shāh Ismā‘īl does describe certain acts as “shirk”, but he did not necessarily believe these to amount to major shirk on their own.[33]

A fatwā of Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd is reproduced in the Fatāwā of Mawlānā Rashīd Aḥmad Ganohī clarifying this:

Question: In the situation that some polytheistic practices that have been mentioned in the treatise Taqwiyat al-Īmān like taking a vow by other than Allāh, kissing a grave, draping a cloth over it, taking an oath by a name beside Allāh’s, and other matters similar to these, have occurred from Zayd, should Zayd be called a disbeliever, and is his blood and property regarded as lawful, and is it permissible to treat him in the way other disbelievers are treated, or not?

Answer: Regarding Zayd as a complete disbeliever, and to treat him in the way of disbelievers, based only on the actions mentioned in the question, is not permissible, and the person who treats him, merely due to the occurrence of the aforementioned actions from him, in the way of disbelievers, is sinful.

All that was written in the treatise Taqwiyat al-Īmān, its detail is that just as it is transmitted in noble ḥadith that faith is a little more than seventy branches and from all the branches the best is to say, “There is no deity but Allah”, and the lowest is to remove anything harmful from the path, and similarly in other narrations it occurs that modesty is a branch of faith, and similarly it occurs in a number of narrations that patience, chivalry, good characteristics are branches of faith, and this is while it has frequently been observed that some of these qualities are found in disbelievers also; for example, many disbelievers are modest and many are well-mannered; thus, due only to finding the trait of modesty in this disbeliever, he cannot be called a believer, nor can he be treated in the way of the believers; but, it should be known that modesty is one branch of faith, and is extremely beloved to Allāh, even if this person is not beloved [to Him] because he is a disbeliever; nonetheless, this habit of his is desirable.

Similarly, since shirk is in opposition to faith, it must also have this number of branches. Thus, merely on account of taking an oath by other than Allāh, one cannot be declared a mushrik, although this act of his is to be understood as an act of shirk, and this action should be swiftly condemned and debased, and the one who does so should be reprimanded in a manner [suited to his condition]; because it is possible that just as this branch of shirk is found in the person, many branches of faith are also present, so because of those branches of faith, he will be accepted by Allāh although this action of his is rejected.

…

Muḥammad Ismā‘īl, author of Taqwiyat al-Īmān, may he be pardoned, wrote this.

Jumāda l-Ūla, 1240 (1824)[34]

In brief, the specific belief that Shāh Ismā‘īl regarded to be true shirk is to believe that someone apart from Allāh has independent powers. Mawlānā Ashraf ‘Alī al-Thānawī explains this idolatrous belief as follows:

Some have the belief that Allāh (Exalted is He) granted a certain creature that is near to Him some independent power to bring benefit and harm in such a manner that in order to bring benefit or harm to his advocate or opponent he is not dependent on a particular will of Allāh. Although if He wanted to stop him, then again the power of Allāh will become dominant. This is just as rulers give their representative governors specific powers in such a way that their administration at that point in time is not dependent on the acceptance of the central ruler. However, if he wanted to stop them, then the ruler’s decree will become dominant. This is belief in causative agency (ta’thīr). The Arabian idolaters had this belief with respect to their false gods.[35]

Finally, it should be noted that there was a forged copy of Radd al-Ishrāk attributed to Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd in which the text is altered to make it appear to be a summary of Muḥammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhāb’s Kitāb al-Tawḥīd. The forgery has misled some to believe that Radd al-Ishrāk derives from Kitāb al-Tawḥīd. Mawlānā Nūr al-Ḥasan Kāndhlawī discusses the forgery in his study on Taqwiyat al-Īmān.[36]

Taqwiyat al-Īmān did certainly contain harsh language as acknowledged by the scholars of Deoband like Mawlānā Rashīd Aḥmad Gangohī[37], Mawlānā Ashraf ‘Alī Thānawī[38] and Mawlānā Anwar Shāh Kashmīrī[39]. The latter even said, “It contained harshness that lessened its benefit”[40], but Mawlānā Thānawī points out that the firm words were used as treatment for the prevailing ignorance of that era.[41]

Historical Narrative: Reconstructing Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd as a Violent Religious Zealot

Asrar Rashid moves onto reconstructing a historical narrative that portrays Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd as a violent extremist and his theological opponent, ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī, as a brave upholder of armed struggle. He states:

When Ismā‘īl al-Dehlawī passed away in 1831. He passed away in Balakot, which is in Pakistan…The people who reside in that area were Muslims. They say he went there to preach Tawḥīd. Some say he went to fight the British. But observing ISIS today, we would note that wherever this creed has spread, it has always spread by the use of the sword…

This is an entirely false narrative. Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd did not go to Balakot to “preach Tawḥīd” or to “fight the British”. In 1826, a couple of years after the Ḥajj, Sayyid Aḥmad Shahīd had started a campaign of Jihād against the Sikhs (whose capital was in Lahore). He travelled to Afghanistan and north-west India to gather support from tribal chiefs. After pushing back some Sikh attacks, he gained the trust and respect of tribal chiefs, who handed over leadership to him. Eventually, he was declared amīr of Peshawar and surrounding areas, and Sharī‘ah was enforced under his command. In 1831, he decided to go to Kashmir to set up a base there to continue the Jihād against the Sikhs. Balakot was en route to Kashmir, and a place where the Muslim fighters felt they could carry out other related activities. However, while at Balakot some Muslims betrayed Sayyid Aḥmad Shahīd and his army, and guided the Sikhs to their whereabouts. A battle ensued, and Sayyid Aḥmad Shahīd and Ismā‘īl Shahīd were martyred at the hands of the Sikhs.[42]

It is Asrar Rashid’s sectarian bias that does not allow him to see this movement as a sincere effort to end Sikh brutality against Muslims and restore Islām to those lands. Through a sectarian lens, he is forced to view Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd as a “Wahhābī”, and thus reinterpret his military activities in light of those of the Arabian Wahhābīs.

Debates Between ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī and Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd

Continuing his historical account, Asrar Rashid says:

When this work Taqwiyat al-Īmān was written, this work like its counterpart in the Middle East Kitāb al-Tawḥīd caused sectarianism which exists until this day …. At that time a prominent scholar known as Imām Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī (raḥimahullāhu ta‘ālā) refuted the work Taqwiyat al-Īmān. He refuted him on a few theological points. One of those points was that Ismā‘īl al-Dehlawī considered it possible for Allāh (subḥānahū wa ta‘ālā), the divine power of Allāh (subḥānahū wa ta‘ālā), to bring out into existence those things which we would deem as being impossible. If something is impossible, Allāh (subḥānahū wa ta‘ālā) He does not will that which is impossible. So, in any given time there could only be one Khātam al-Nabiyyīn, one finality of prophets. The Messenger of Allāh (ṣallallāhu ‘alayhi wasallam) who is described in al-Quran al Karīm as Khātam al-Nabiyyīn the finality of prophets, there can only be one finality of prophets in any given time. Imām Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī (raḥimahullāh) refuted Ismail Dehlawi on this point where he considered it possible for Allah (subḥānahū wa ta‘ālā) to bring multiple prophets like our Messenger (ṣallallāhu ‘alayhi wasallam). Why is this considered from the realm of impossibility? One reason being there can only ever be one Khātam al-Nabiyyīn finality of prophets… Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī (raḥimahullāhu ta‘ālā) wrote Taḥqīq al-Fatwā, he wrote Imtinā‘ al-Naẓīr refuting the ideology of Ismā‘īl al-Dehlawī. And numerous other ‘ulamā’ also wrote refutations against Ismā‘īl al-Dehlawī at that time.

ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī (1797 – 1861), about whom more will be written below, wrote a brief refutation of Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd in 1826, to which the latter wrote a response called Yak Rozah. The debate occurred in response to a sentence of Taqwiyat al-Īmān. Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd was discussing a mistaken conception of shafā‘ah (intercession), called “shafā‘ah al-wajāhah” (intercession of status), in which it is believed that Allāh suppresses His original intent to punish one deserving of punishment because someone holding a high status intercedes, and He does not wish to cause disruption in His Kingdom on account of displeasing the intercessor. As Shāh Ismā‘īl explains, one who holds such a belief is a “true mushrik and a complete ignoramus, and has not understood the meaning of divinity in the slightest, and has not realised the greatness of this Owner of the Kingdom.”[43] Then, explaining the power and greatness of Allāh, he said: “It is the nature of this King of Kings that in a single moment, had He so wished with one command of ‘Kun’, He would create thousands of prophets, saints, jinn and angels equal to Jibra’īl, upon him peace, and Muḥammad, Allāh bless him and grant him peace; and would turn the whole universe from the throne to the earth upside down and put another creation in its place.”[44] He goes onto say that if all creatures were like Jibra’īl and the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him), this would not increase in the lustre of Allāh’s kingdom, and similarly if all creatures were devils and dajjals this would not decrease from the lustre of His Kingdom.[45]

In context, Shāh Ismā‘īl’s statement is justifiable, given that he was trying to drive home the point to readers (who would entertain the belief in “shafā‘ah al-wajāhah”) that Allāh has no need for His creation and does not depend on them in the slightest. But ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Haqq Khayrābādī picked up on a technical point, claiming that it is intrinsically impossible for there to be an equal (mithl/naẓīr) to Muḥammad (peace and blessings be upon him), so the scenario Shāh Ismā‘īl presented was not even hypothetically possible.

In Yak Roza, Shāh Ismā‘īl wrote a response. He explains that for an equal to come into existence is included within Divine Power but its materialisation is impossible. He presents evidence from the Qur’ān and from reason. From the Qur’ān, he cites the verse: “Is not He Who created the heavens and the earth capable of creating the like of them [i.e. human beings]? Of course!” (36:81) This verse shows Allāh can create an equal or a like of each human being, which of course includes the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him).[46]

From a rational point of view, if ever something is mumkin (intrinsically possible), then its equal is also intrinsically possible. In terms of the basic nature (māhiya) of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) and his characteristics of perfection, there is no intrinsic impossibility of a likeness or equal being created.[47]

Shāh Ismā‘īl also offers several responses to the point that the Prophet is “Khātam al-Nabiyyīn”, and thus cannot have an equal. One response he offers is that it is in Allāh’s power to create a realm of existence that is not linearly connected in time with this realm, where the equal will also be a final prophet. Thus, it is not beyond the realm of conceivability and thus possibility that an equal of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) could be created. Thus, it is intrinsically possible though extrinsically impossible.[48]

It is not the case, as Asrar Rashid tries to make out, that the scholars in general refuted Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd. A close friend of ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī, Muftī Ṣadr al-Dīn al-Dehlawī (1790 – 1868) [who was a teacher of Mawlānā Rashīd Aḥmad Gangohī], rivalled ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Haqq in his expertise of the rational sciences, having studied with Mawlānā Faḍl al-Imām Khayrābādī (ꜥAllāmah Fadl al-Ḥaqq’s father) also. He approved of Taqwiyat al-Īmān[49] and disapproved of ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq’s refutations, as reported by one of his students, Ṣiddīq Ḥasan Khān (1832 – 1890).[50]

Later, ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī wrote a more detailed refutation called Taḥqīq al-Fatwā. Sayyid Ḥaydar ‘Alī Tonkī (1788 – 1856), an expert in philosophy and logic, refuted it in a work called al-Kalām al-Fāḍil al-Kabīr ‘alā Ahl al-Takfīr.[51] Ṣiddīq Ḥasan Khān comments: “The reality is that the truth in these debates are in the hand of Sayyid [Ḥaydar ‘Alī Tonkī], not Shaykh [Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī], as evident to one who refers to their books with objectivity, and I have seen most of them.”[52]

A non-partisan scholar from a slightly later era, Pīr Mehr ‘Alī Shāh (1859 – 1937), was asked about this debate. Before offering his opinion, he said:

My aim here is to present what is in my mind on the possibility or impossibility of an equal to the Prophet (Allāh bless him and grant him peace), not to deem either of the two groups, Ismā‘īliyya or Khāyrābādiyya, correct or incorrect. May Allāh repay their efforts. The writer of these lines regards both of them to be rewarded.[53]

Was there a Verbal Debate Between ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī and Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd?

Asrar Rashid goes onto say:

By the way he debated Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī (raḥimahullāhu ta‘ālā) in the Grand Masjid of Delhi also and Imām Faḍl al-Ḥaqq silenced him.

Mawlānā Nur al-Ḥasan Kāndhlawī shows that this too is a myth. ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī and Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd only engaged in a written debate, not a verbal one. ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī first wrote a response in 1826, after Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd had already left Delhi for Jihād against the Sikhs. They did not debate before this.[54]

Historical Narrative: Reconstructing ‘Allāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī as an Anti-British Revolutionary

Asrar Rashid continues:

But afterwards Imām Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī (raḥmatullāh ‘alayhi) took part in al-thawrat al-hindiyya, the Indian revolution. This was a revolt against the British colonialists. In which year? In the year 1857. Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī (raḥimahullāhu ta‘ālā) was one of the leading proponents of revolt against the British. Now when people rewrite history what they do is that they attempt to change the facts. One example of this is the university known as Nadwat al-‘Ulamā’. This place, Nadwa, when one of the scholars known as ‘Abdul Ḥayy, not to be confused with Abul Ḥasanāt ‘Abdul Ḥayy Laknawī…the father of Abul Ḥasan al-Nadwī, he wrote a book called Nuzhat al-Khawāṭir. In that book, when writing the biography of Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī (raḥimahullāhu ta‘ālā), he states: “He only revolted against the British because the British stopped paying him.” This is what you call a rewriting of history….But Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī (raḥimahullāhu ta‘ālā) was a sincere scholar who was then martyred by the British in 1861 on the Andaman island. They hung him, raḥimahullāh ta‘ālā.

This entire account is very problematic. To start with, ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī died a natural death after being imprisoned on the Andaman Islands. He was not hanged. Siddīq Hasan Khān, who was a contemporary of ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī and saw him, says simply that “he died” on the island.[55] Other biographies mention the same. Can Asrar Rashid prove that ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī was executed by the British and not just imprisoned on the island?

The assertion that Nuzhat al-Khawāṭir reports that ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī revolted against the British because of not being given payment also seems to be outright fabrication. One can read through the short biography of ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī in Nuzhat al-Khawāṭir, and find nothing of the sort.[56] In fact, Nuzhat al-Khawāṭir doesn’t even say he revolted against the British! It just says “he was accused of rebelling against the English government…”[57] This description – that his involvement in the rebellion was merely an unproven allegation – seems to be more accurate.

The contemporary German professor, Jamal Malik, has written a reliable sketch of the life of ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī, pieced together from the latter’s letters, notes and unpublished books.[58] ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī was an employee of the British whom he served from around 1815. He, however, was not fond of the arrogance and rudeness of the British. Thus, in 1831, he quit his service. But just before the outbreak in 1857, he resumed his service, and served in a high British administrative position in Lucknow.

On his alleged involvement in the 1857 rebellion, Jamal Malik says: “[A]part from the claims of his followers, there is no definitive evidence about the extent of Khairabadi’s alleged involvement in subversive activities, and no such claims could be supported on the basis of the available material, i.e., letters, poems, autobiographical accounts.”[59]

A fatwā was drafted in Delhi and signed by some prominent scholars (possibly, under threat or coercion), including Muftī Ṣadr al-Dīn al-Dehlawī (who was mentioned earlier). The fatwā supported revolting against the British if they kill Muslims and appropriate their wealth. At the time the fatwā was signed, ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī was not even in Delhi. So, it appears he did not sign the fatwā.

One of the leaders of the rebellion of 1857 was a Mīr Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Shahājānpūrī who shared the same name as ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī. Mistaking the latter for the former seems to have been the reason he was imprisoned. Descendants of ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī report that he appealed his sentence, and was even meant to be released, but died shortly before the release date.[60] Jamal Malik concludes: “Whether Fadl-e Haqq took active part in the revolt or not is still a matter of debate. In fact, his autobiographical notes and poems permit no such conclusion.”[61] He further says: “In the case of Khairabadi, one may suspect a judicial error on the part of the British administration. This is more likely, since there had been a namesake (Sayyid Fadl-e Haqq Shahjahanpuri) active in 1857. This error would provide evidence of the profound ignorance or even vindictiveness of the British.”[62]

Hence, Asrar Rashid’s attempt at rebranding ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī as a leading proponent of the 1857 revolution is of course a stretch. He was a fiery theologian and British employee, never proven to have rebelled. It is obvious the only reason ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī is rebranded in this way is to portray him in a positive light vis a vis his theological opponent Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd.

Māwlānā Qāsim Nānotwī

Asrar Rashid further says:

At that point was the inception of a Dārul ‘Ulūm, a university, in fact two notorious universities, one is in Aligarh…and another one which is known as Dārul ‘Ulūm Deoband…Imām Aḥmad Riḍā Khān (raḥimahullāhu ta‘ālā) was unrivalled in ‘Ilmul Kalām, in defending the creed of Ahlus Sunnah wa l-Jamā‘ah, but especially after the period of 1870. Why 1870? Because one of the founders of Dārul ‘Ulūm Deoband whose name was Qāsim Nānotwi, he wrote a notorious book known as Taḥdhīrun Nās. Taḥdhīrun Nās caused a storm in India also. And in fact one of those scholars who refuted Tahdhirun Nās is ‘Abdul Ḥayy al-Laknawi Abul Ḥasanat who passed away in 1304. But the strange thing is when you read Nuzhat al-Khawāṭir of ‘Abdul Ḥayy, the other ‘Abdul Ḥayy, when they give the biography of ‘Abdul Ḥayy al-Laknawī, they do not mention any of this. These things are blotted out. But the works are available.

This account is either very misleading or downright falsehood. Asrar Rashid makes it appear that ‘Abd al-Ḥayy al-Laknawi (1848 – 1886) wrote a refutation of Taḥdhīr al-Nās (and thus this should have been mentioned in his biography in Nuzhat al-Khawāṭir), while this is not the case.

The reality is that there was an alleged debate between Māwlānā Qāsim Nānotwī (1833 – 1880) and Māwlānā Muḥammad Shāh Punjābī on the contents of Taḥdhīr al-Nās. The arguments of both sides were then presented to some individuals, who favoured the view of Māwlānā Muḥammad Shāh Punjābī. This was then published as Ibṭāl Aghlāṭ Qāsimiyyah after the demise of Māwlānā Qāsim Nānotwī.

The disagreement was over the meaning of “Khātam al-Nabiyyīn”. The general understanding is it means simply “the last prophet”, but Mawlānā Qāsim Nānotwī believed it to have a broader meaning that includes the notion that prophethood culminates at the Prophet (peace and blessing be upon him), whereby his prophethood was granted directly by Allāh while the prophethood of all other Prophets was attained via the intermediary of his prophethood. This, he said, is the esoteric meaning (baṭn) of “Khātam al-Nabiyyīn”. He did not believe this to contradict chronological finality, and in fact considered chronological finality to be the accepted outward meaning (ẓahr) of “Khātam al-Nabiyyīn”, as well as part of the esoteric meaning either by extension or implication.[63] The signatories of Ibṭāl Aghlāṭ Qāsimiyyah considered Mawlānā Qāsim Nānotwī’s interpretation to be incorrect. ‘Abd al-Ḥayy al-Laknawi was allegedly one of these signatories.

The real cause of sectarianism in this affair, however, was unjustified takfir. Takfīr on this subject was initiated by Naqī ‘Alī Khān (1830 – 1880), the father of Aḥmad Riḍā Khān Barelwī (1856 – 1921)[64], and then followed by Aḥmad Riḍā Khān himself. The latter claimed that Mawlānā Qāsim Nānotwī denied the finality of prophethood – which is a clear misrepesentation. In the very work Taḥdhīr al-Nās, Mawlānā Qāsim Nānotwī declared belief in chronological finality as being from the absolute essentials of religion denying which is kufr. He writes:

Therefore, if [sealship] is absolute and general, then the establishment of chronological finality is obvious. Otherwise, accepting the necessity of chronological finality by implicative indication is immediately established. Here, the explicit statements of the Prophet, like: ‘You are to me at the level of Hārūn to Mūsā, but there is no prophet after me,’ or as he said, which apparently is derived from the phrase ‘Khātam al-Nabiyyīn’ in the manner mentioned earlier, are sufficient on this subject, because it reaches the level of tawātur. Furthermore, consensus (ijma‘) has been reached on this.

Although the aforementioned words were not transmitted by mutawātir chains, but despite this lack of tawātur in the words, there is tawātur in the meaning just like the tawātur of the number of rak‘āt of the obligatory prayers, the witr prayer etc. Although the words of the narrations stating the number of rak‘āt are not mutawātir, just as the one who denies that is a kāfir, in the same way, the one who denies this is a kāfir.[65]

Thus, even some scholars affiliated to Aḥmad Riḍā Khān (and who would not be partisan to Mawlānā Qāsim Nānotwi) have also acknowledged that Mawlānā Qāsim Nānotwī does not deny the essential belief of Islām on the chronological finality of prophethood. One such eminent scholar, Pir Karam Shah Azhari (1918 – 1998), says:

I do not think it correct to say that Mawlānā Nānotwī (may Allah have mercy on him) denied the belief in the finality of prophethood, because these passages (of Tahdhīr al-Nās), by way of the clear meaning of the text and its indication, show without doubt that Mawlānā Nānotwī (may Allah have mercy on him) had certainty that chronological finality of prophethood is from the necessities of religion, and he regarded its evidences as categorical and mutawātir. He has stated this matter explicitly, that the one who denies chronological finality of prophethood of the Prophet (Allah bless him and grant him peace) is a kāfir and outside the fold of Islam.[66]

Notice, he says “without doubt” Mawlānā Qāsim Nānotwī had certainty in the chronological finality of prophethood and that it is from the necessities of religion. This is in contrast to Aḥmad Riḍā Khān’s definitive verdict of kufr on Mawlānā Qāsim Nānotwī precisely for denying the chronological finality of prophethood.

Another prominent scholar from Pakistan unaffiliated with the school of Deoband, Khwājah Qamar al-Dīn Siyālwī (1906 – 1981), said:

I have seen Taḥdhīr al-Nās. I regard Mawlānā Qāsim Ṣāḥib Nānotwī to be a Muslim of the highest degree. I take pride in the fact that his name is found in my chain of ḥadīth. In elaborating the meaning of ‘Khātam al-Nabiyyīn’, the mind of objectors did not understand the depth to which Mawlānā’s mind reached. A hypothetical proposition was treated as a factual one.[67]

In short, while Mawlānā Nānotwī offers a less common interpretation of the term “Khātam al-Nabiyyīn”, his interpretation does not violate any established belief of Islām, least of all the chronological finality of the prophethood of Muḥammad (peace and blessings be upon him) and that prophethood terminated at him. Even amongst those who are from the same school as Mawlānā Qāsim Nānotwī, some have conceded that there can be legitimate disagreement with him on this subject[68], but there is no grounds for takfīr. It should be noted that Mawlānā Qāsim Nānotwī, though in a minority, was not unprecedented in his view on the meaning of “Khātam al-Nabiyyīn”.[69]

The Seeds of Sectarianism

Asrar Rashid continues:

This theological debate continued until we know that this culminated in Imām Aḥmad Riḍā Khān refuting Rashīd Aḥmad Gangohī, Ashraf ‘Alī Thānawī, & Khalīl Aḥmad Ambhetwī, as well as one of the founders Qasim Nanotwi…

It is important to add that Aḥmad Riḍā Khān did not only “refute” these senior imāms, but made takfīr against them. The takfir of Mawlānā Qāsim Nānotwī was discussed briefly above. The three remaining takfīrs will be discussed in brief below.[70]

Mawlānā Rashīd Aḥmad Gangohī

On Mawlānā Rashīd Aḥmad Gangohī (1829 – 1905), Aḥmad Riḍā Khān Barelwī claimed that he wrote a fatwā in which he did not censure the view that lying has actually occurred in Allāh’s speech, and in fact lent support to it. Aḥmad Riḍā Khān states he has seen this alleged “fatwā” in the handwriting of Mawlānā Gangohī and with his seal. Moreover, he states that the fatwā along with its refutation has been published several times. The reality, however, is that this so-called “fatwā” was circulated only amongst detractors of Mawlānā Gangohī. It is not found in any of his published fatwās, nor is it recognised by any of his students.[71] In fact, in direct contradiction to this alleged “fatwā”, Mawlānā Gangohī explicitly said in his published Fatāwā that the one who believes an actual lie has occurred in Allāh’s speech, or that Allāh is characterised by “false speech”, is a kāfir.[72]

Mawlānā Gangohī himself was unaware of this allegation until the last moments of his life. In the year 1905, Mawlānā Gangohī’s student, Mawlānā Murtaḍā Ḥasan Chāndpūrī (1868 – 1951), became aware of this alleged “fatwā” and the claims being made. He immediately sent a copy to Mawlānā Gangohī and asked for clarification. Mawlānā Gangohī replied: “I had no knowledge of this. This allegation is…an error. Allāh forbid that I can say such!” Mawlānā Murtaḍā Ḥasan Chāndpūrī documents this in his Tazkiyat al-Khawāṭir.[73]

In short, the allegation against Mawlānā Gangohī is based on a fabricated fatwā that he himself denied, that is not known to his students and that contradicts his explicit fatwās.

Mawlānā Khalīl Aḥmad Sahāranpūrī

On Mawlānā Khalīl Aḥmad Sahāranpūrī (1852 – 1927), Aḥmad Riḍā Khān claimed that he wrote in Barāhīn Qāṭi‘ah that (Allāh forbid!) Shayṭān’s knowledge is superior to the Prophet’s. In Barāhīn Qāṭi‘ah, Mawlānā Khalīl Aḥmad Sahāranpūrī was responding to another work, Anwār Saṭi‘ah. The author of the latter work apparently argues that since the Shayṭān is known to have extensive knowledge of people’s actions and so on, such knowledge should not be denied for the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) given his greater status. Mawlānā Khalīl Aḥmad Sahāranpūrī responds that knowledge of such things cannot be determined for the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) based on analogies of this nature.[74]

As can be seen, the discussion is about a specific type of knowledge. This is absolutely clear from the context and from explicit passages of Barāhīn Qāṭi‘ah. Mawlānā Khalīl Aḥmad Sahāranpūrī is not stating (as suggested by Aḥmad Riḍā Khān) that Shayṭān possesses greater knowledge than the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) in a general and absolute sense. But, in matters that are not the basis of excellence or virtue in knowledge, Shayṭān may be aware of certain aspects of them that the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) was not aware of. For example, Shayṭān may be aware that a certain person has robbed a bank including the means and techniques by which he accomplished this, while this knowledge was not given to the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him); this in no way means Shayṭān is superior in knowledge to the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him).

As he clarifies in a later work called al-Muhannad, Mawlānā Khalīl Aḥmad Sahāranpūrī states that excellence in knowledge is based on greater knowledge of Allāh, His Dīn and the outer and inner aspects of Sharī‘ah. No one equals the rank of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) in such knowledge. In things that are not the basis of virtue or excellence in knowledge, however, there is nothing surprising in another knowing something that is unknown to the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him). [75]

Mawlānā Ashraf ‘Alī Thānawī

On Mawlānā Ashraf ‘Alī Thānawī (1863 – 1943), Aḥmad Riḍā Khān claimed that he wrote in his Ḥifẓ al-Īmān that (Allāh forbid!) madmen, children and animals possess knowledge of the unseen equal to that of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him). This too is far from what Mawlānā Ashraf ‘Alī Thānawī actually said. In Ḥifẓ al-Īmān, he was discussing the question of using the title “‘Ᾱlim al-Ghayb” (knower of the unseen) for the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him). He firstly explains that this is a technical term in Sharī‘ah which means a being that possesses knowledge of unseen realities without the need for any means or instrument. Such a characteristic is of course exclusive to Allāh, because everyone apart from Allāh acquires knowledge of unseen realities only via a means and instrument.

He then explains that “unseen” (ghayb) can refer to things that are hidden from the senses in a general sense, whether acquired by a means or not. But even with this interpretation, the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) should not be called “‘Ᾱlim al-Ghayb”. He reasons that the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) of course does not possess knowledge of all unseen realities, while the quality of possessing knowledge of some unseen realities is not exclusive to the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him). Possessing knowledge of some unseen realities is something found in Zayd and ‘Amr, children, madmen and animals, because they all possess knowledge of some things hidden to others – does this now mean that they are all to be called “‘Ᾱlim al-Ghayb”?![76]

As can be seen, Mawlānā Thānawī does not state that “madmen, children and animals possess knowledge of the unseen equal to that of the Prophet” as was alleged. Rather, he simply states that they possessed knowledge of some unseen realities; and thus the mere possession of knowledge of some unseen realities is not exclusive to the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him).

When Mawlānā Thānawī was asked about the passage of Ḥifẓ al-Īmān and if he had ever written that “madmen, children and animals possess knowledge of the unseen equal to that of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him)”, he replied: “I did not write this revolting content in any book. Let alone writing it, this thought never crossed my heart. Nor is it the necessary conclusion of any passage of mine, as I will explain later. Since I understand this content to be revolting…how can it be my intent? That person who believes this, or without belief utters it explicitly or implicitly, I believe this person to be outside the fold of Islam because he has denied decisive texts and lessened the Revered Joy and Pride of the World, the Prophet, Allah bless him and grant him peace.”[77]

Aḥmad Riḍā Khān nonetheless declared Mawlānā Thānawī a disbeliever on this account. In fact, he went as far as to say if anyone doubts the disbelief of these individuals, he is a disbeliever himself![78]

Testimony of Non-Partisan ‘Ulamā’

Those who do not have a stake in this conflict have also regarded the ‘ulamā’ of Deoband highly. One of the great spiritual masters of the era was Shaykh Faḍl al-Raḥmān Ganjmurādābādī (1794 – 1895) with whom several early scholars of Deoband were connected, including Muftī ‘Azīz al-Raḥmān Deobandī (1859 – 1928), Mawlānā Ḥusayn Aḥmad Madanī and Mawlānā Murtaḍā Ḥasan Chāndpūrī. His khalīfah (Shāh Tajammul Ḥusayn Bihārī) mentioned that Shaykh Faḍl al-Raḥmān Ganjmurādābādī held Mawlānā Qāsim Nānotwī and Mawlānā Rashīd Aḥmad Gangohī in high regard, believing them to be from the Awliyā’.[79] The testimony of other non-partisan ‘ulamā’ and Ṣufīs have been collected by Sayyid Nafīs al-Ḥusaynī (1933 – 2008) in his Ḥikāyāt Mehr o Wafā: Buzurgāne Deoband Apne Ham‘aṣr ‘Ulamā’ wa Maskā’ikh Kī Naẓr Mein.

Conclusion

Asrar Rashid paints Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd as a violent zealot who abandoned the Sunnī methodology of his forefathers, came under the tutelage of Wahhābī missionaries, and wrote Taqwiyat al-Īmān under the influence of foreign Wahhābī ideology. As shown above, this entire narrative is false.

Asrar Rashid paints ꜥAllāmah Faḍl al-Ḥaqq Khayrābādī as an upright scholar who supported the 1857 revolution against the British, while this narrative too is deeply flawed. Further, Asrar Rashid puts the blame of “sectarianism” wholly at the hands of Shāh Ismā‘īl Shahīd and those Aḥmad Riḍā Khān Barelwī opposed, completely ignoring the takfīr which fanned the flames of disunity amongst the Sunnīs of the Indian Subcontinent.

Asrar Rashid’s partisanship and sectarian bias towards (mis)readings of history and theology is undeniable. His claims to being objective and unbiased are just that: claims, with no truth to them. It is strange that a lecture on the history of sectarianism would contain so many inaccuracies, and hence peddle a narrative that is more fictitious than factual. What is also evident is the sheer irony of claiming to be objective whilst regurgitating calamitous takfīr-steeped rhetoric, a clear indication that Asrar Rashid is merely repackaging old arguments in a more palatable way.

Objectivity on this issue demands, as a fundamental prerequisite, that unsubstantiated assumptions which lead to unjustified takfīr be clearly rejected. Giving new life to these old arguments is the cause of sectarianism, not its cure, and the obsession with creating distrust of a whole community of subcontinent Sunnī scholarship only serves to fuel divisive, sectarian sentiments that are both unwanted and unnecessary.

If Asrar Rashid has a change of heart and decides to sincerely challenge his false/misleading claims, assumptions and narratives based on the above evidences (much of which have been available online for years), this would be a welcome change, and in the spirit of objectivity, it would be hoped he casts aside the sectarian takfīrī rhetoric and truly embraces the wider Sunnī family.

Footnotes

[1] “History of Sectarianism: Wahabi, Deobandi, Qadiyani, Khilafat Movement”

[2] Majallah Aḥwāl wa Ᾱthār, no. 20-21. A PDF is available.

[3] Ibid. p. 22

[4] Ibid. p. 98

[5] Ibid. p. 102

[6] Ibid. p. 105

[7] Sīrat Sayyid Aḥmad, 1:353

[8] Majallah Aḥwāl wa Ᾱthār, no. 20-21, p. 22

[9] “The Deobandi-Barelawi Paradigm Shift and Lateral Thinking”

[10] Ibid. p. 105

[11] This is a slip of the tongue. He meant to say “1779”.

[12] This is also a slip of the tongue. He meant to say “1792”.

[13] Islamic Reform and Revival in Nineteenth Century India, Yoda Press, p. 39

[14] Naqsh e Ḥayāt, p. 431-2

[15] Sīrat e Sayyid Aḥmad, 1:342-365

[16] Taqwiyat al-Īmān, Qasid Kitab Ghar, p. 82

[17] A PDF of which is available

[18] ‘Abaqāt, p. 174:

قد وقع بين كل فن تفرق واختلاف، وهو على نحوين، تفرق بين المبطلين والمحقين كالتفرق بين فقهاء الشيعة و أهل السنة والأشاعرة والمعتزلة أو الوجودية الملاحدة والوجودية العرفاء أو بين من يستعين في مراقاباته بالخمور والمسكرات وبين من يستعين فيها بالأذكار والصلاة أو بين من يعالج عجب القلب بترك شعائر الشرع وبين من يعالجه بملاحظة المعاصي أو القصور فى الطاعات وهكذا فقس، فالحكم في مثل هذا التفرق وجوب تصويب أحد الجانبين وتخطئة الآخر كذلك، وتفرق بين أهل الحق كالتفرق بين الأئمة الأربعة أو بين الأشعرية والماتريدية أو بين الوجودية الورائية والشهودية الظلية أو بين أهل الطرق، فالحكم فيه أن كل واحد منهم في أكثر المسائل على طريق حق، ولكل واحد هو موليها فاستبقوا الخيرات، فمن اتبع واحدا منهم فاز بالمقصود

[19] Yak Rozah, p. 2

[20] ‘Abaqāt, p. 3

[21] Ibid.

[22] Al-Ḥiṭṭah fi l-Ṣiḥāḥ al-Sittah, Dār al-Jīl, p. 258

[23] See: https://www.deoband.org/2010/09/aqida/allah-and-his-attributes/the-reality-of-shirk-its-manifestations-and-its-types/

[24] It is based on a misreading of a passage from Īḍāḥ al-Ḥaqq al-Ṣarīḥ

[25] ‘Abaqāt, p. 35, 102

[26] Mathnawī Silk e Nūr; quoted in Shāh Ismā‘īl Muḥaddith al-Dehlawī , p. 132

[27] Naqsh e Ḥayāt, p. 432

[28] See: Naqd al-Ru’yat al-Wahhābiyyah li l-Tawḥīd by ‘Uthmān Nābulūsī

[29] Radd al-Ishrāk, p. 15-6:

اعلم أن الإشراك – الذي أنزل الكتب الإلهية لإبطاله وبعث الأنبياء لمحقه – ليس مقصورا على أن يعتقد أحد أن معبوده مماثل للرب تبارك وتعالى في وجوب الوجود، أو إحاطة العلم بجميع الكائنات، أو الخالقية لأصول العوالم كالسماء والأرض، أو التصرف في جميع الممكنات، فإن هذا الإعتقاد ليس من شأن الإنسان أن يتلوث به، اللهم (إلا) أن كان ممسوخا كفرعون وأمثاله، وليس لأحد أن يذعن بأن الكتب الإلهية إنما نزلت والأنبياء إنما بعثت لأجل إصلاح أمثال هؤلاء الممسوخين فقط، كيف ومشركوا العرب الذين سماهم النبي صلى الله عليه وسلم بالمشركين وقاتلهم وأراق دماءهم وسبى ذراريهم ونهب أموالهم لم يكونوا مذعنين بهذا الإعتقاد، بدليل قوله تعالى: ((قل من بيده ملكوت كل شيء وهو يجير ولا يجار عليه إن كنتم تعلمون، سيقولون: الله، فل: فأنى تسحرون؟)) وأمثال هذه الآية كثيرة جدا. بل معناه أن يشرك أحدا من سوى الله معه تعالى فى الألوهية أو الربوبية. ومعنى الألوهية أن يعتقد في حقه أنه بلغ فى الإتصاف بصفات الكمال من العلم المحيط أو التصرف بمجرد القهر والإرادة مبلغا جل عن المماثلة والمجانسة مع سائر المخلوقين، وذلك بأن يعتقد أنه ما من أمر يحدث سواء كان من الجواهر أو الأعراض فى الأقوال أو الأفعال أو الإعتقاد أو العزائم والإرادات والنيات إلا وهو ممتنع أن يغيب من علمه وهو شاهد عليه أو يعتقد أنه يتصرف فى الأشياء بالقهر أي: ليس تصرفه فى الأشياء من جملة الأسباب بل هو قاهر على الأسباب. ومعنى الربوبية أنه بلغ في رجوع الحوائج واستحلال المشكلات واستدفاع البلايا بمجرد الإرادة والقهر على الأسباب مبلغا استحق به غاية الخضوع والتذلل، أي: ليس للتذلل لديه والخضوع عنده حد محدود، فما من تذلل وخضوع إلا وهو مستحسن بالنسبة إليه وهو مستحق له. فتحقق أن الإشراك على نوعين: إشراك فى العلم وإشراك فى التصرف. ويتفرع منهما: الإشراك فى العبادات، وذلك بأنه إذا اعتقد في أحد أن علمه محيط وتصرفه قاهر فلا بد أنه يتذلل عنده ويفعل لديه أفعال التعظيم والخضوع، ويعظمه تعظيما لا يكون من جنس التعظيمات المتعارفة فيما بين الناس، وهو المسمى بالعبادة. ثم يتفرع عليه: الإشراك فى العادات وذلك بأنه إذا اعتقد أن معبوده عالم بالعلم المحيط متصرف بالتصرف القهري لا جرم أنه يعظمه في أثناء مجارى عاداته بأن يميز ما ينتسب إليه كاسمه وبيته ونذره وأمثال ذلك من سائر الأمور بتعظيم ما. وقد رد الله تعالى في محكم كتابه أولا وعلى لسان نبيه صلى الله عليه وسلم ثانيا على جميع أنواع الشرك على أصوله وفروعه وذرائعه وأبوابه ومجمله ومفضله

[30] هذه المقدمة لا غبار عليها، والفرق شاسع جدًأ بين كلامه وكلام محمد بن عبد الوهاب

[31] https://www.deoband.org/2010/09/aqida/allah-and-his-attributes/the-reality-of-shirk-its-manifestations-and-its-types/

[32] Taqwiyat al-Īmān, p. 8

[33] Majallah Aḥwāl wa Ᾱthār, no. 20-21, p. 88

[34] Al-Ta’līfāt al-Rashīdiyya p.86-8

[35] https://www.deoband.org/2013/01/aqida/allah-and-his-attributes/the-peak-of-comprehension-on-the-categories-of-polytheism/

[36] Majallah Aḥwāl wa Ᾱthār, no. 20-21, p. 75-9

[37] Ta’līfāt Rashidiyya, p. 90

[38] Imdad al-Fatāwā, Zakariyyā Book Depo, 11:574

[39] Fayḍ al-Bārī, 1:252

[40] Ibid.

[41] Imdad al-Fatāwā, Zakariyyā Book Depo, 11:574

[42] Life Sketch of Syed Ahmed Shahid, p. 23-5

[43] Taqwiyat al-Īmān, p. 44

[44] Ibid.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Yak Rozah, p. 2-3

[47] Yak Rozah, p. 4-5

[48] Ibid. p. 10-2

[49] Majallah Aḥwāl wa Ᾱthār, no. 20-21, p. 35; Mawlānā Nūr al-Ḥasan shows this support is authentic from him

[50] Abjad al-‘Ulūm, 3:254

[51] Majallah Aḥwāl wa Ᾱthār, no. 20-21, p. 153

[52] Abjad al-‘Ulūm, 3:248

[53] Fatāwā Mehria, p. 11

[54] Majallah Aḥwāl wa Ᾱthār, no. 20-21, p. 152-3

[55] Abjad al-‘Ulūm, 3:254

[56] Nuzhat al-Khawāṭir, 1063-5

[57] Ibid,

[58] Letters, prison sketches and autobiographical literature; The Indian Economic & Social History Review 03 2006 ; vol. 43, 1 : pp. 77-100. A PDF of this article is available at request.

[59] Ibid. p. 87

[60] P. 88

[61] P. 90

[62] P. 96

[63] See Dr Khalid Maḥmūd’s introduction to Taḥdhīr al-Nās, p.7-29. See also: Mawlānā Qāsim Nānotwī on Khatm al-Nubuwwah – Response to Asrar Rashid – Basair.net

[64] For details, see Taḥdhīr al-Nās Eik Taḥqīqī Mutāla‘ah, p. 11-20; unjustified takfir was made earlier on a related issue which was refuted by Sayyid Ḥaydar ‘Alī Tonkī (1788 – 1856) in al-Kalām al-Fāḍil al-Kabīr ‘alā Ahl al-Takfīr.

[65] Taḥdhīr al-Nās, p. 56

[66] Tahdhīr un-Nās Merī Nazar Meh, p. 58

[67] Dhol kī Ᾱwāz; quoted in Ḥikāyāt Mehr o Wafā, p. 40

[68] Taḥdhīr al-Nās Eik Taḥqīqī Mutāla‘ah, p. 27

[69] See: The Decisive Debate, p.86-7; available as a PDF online. See also: Sectarianism and Its Roots in the Indian Subcontinent | Ahlus Sunnah Forum (basair.net)

[70] For detailed refutations, see the works of Mawlānā Murtaḍā Ḥasan Chāndpūrī, al-Shihāb al-Thāqib of Mawlānā Ḥusayn Aḥmad Madani and Fayṣlah Kun Munāẓarah by Mawlānā Manẓūr Nu‘māni. The latter has been translated as “The Decisive Debate” and is available as a PDF online.

[71] al-Shihāb al-Thāqib, p. 249, 259

[72] Ta’līfāt Rashīdiyyah, p. 96; al-Shihāb al-Thāqib, p. 260

[73] Majmū‘ah Rasā’il Chāndpūrī, 1:106

[74] Barāhīn Qāṭi‘ah, p. 55-6

[75] Al-Muhannad ‘ala l-Mufannad, Dār al-Fatḥ, p. 71-3

[76] Ḥifẓ al-Īmān, p. 14-5

[77] Basṭ al-Banān; quoted in Fayṣlah Kun Munāẓarah, p.171-2

[78] Ḥusām al-Ḥaramayn, p. 64

[79] Kamālāt Raḥmānī; quoted in Ḥikāyāt Mehr o Wafā, p. 5

Good article. If others apart from Imam Ahmed Riza Khan (rh) didn’t say these scholars were kafir, why can’t we just follow their opinion? I Don’t think we need this calling everyone kafir kind of attitude here in England especially. You can disagree but don’t call each other kafir

Most engaging analysis – Although this raises more questions than it answers

Pīr Sayyid Jamāꜥat Alī Shāh (1834–1951), a prominent Naqshbandi shaykh of Pakistan, actually studied in Saharanpur under Mawlānā Muḥammad Maẓhar Nanautawī (1823-1885), the founder of the Maẓāhir al-ꜥUlum seminary and a disciple of Mawlānā Rashīd Aḥmad Gangohī.

His son and first successor, Pīr Sayyid Muḥammad Ḥusayn Shāh, studied ḥadīth under Muftī Kifāyatullāh al-Dehlawī at Madrasah Amīniyah, Delhi. Shaykh al-Hind Mawlānā Maḥmūd al-Ḥasan came for the graduation ceremony the year Pīr Sayyid Muḥammad Ḥusayn Shāh was graduating. As there were no turbans left for this very humble student, Shaykh al-Hind Mawlānā Maḥmūd al-Ḥasan took off his own hat, placed it on Pīr Sayyid Muḥammad Ḥusayn Shāh’s head and then tied his own turban on him. Likewise, he signed Pīr Sayyid Muḥammad Ḥusayn Shāh’s authorisation certificate.

where is this from? it should be from original sources, not third parties.

its not third party sources. written by his grandson:

Sīrat Amīr-i-Millat Pīr Sayyid Jamāꜥat ꜥAlī Shāh, pg. 59 and pg. 673.

A PDF of the work is available to verify the quotes:

https://ia600108.us.archive.org/27/items/SeeratAmeerEMillatPirSyedJamatAliShah/Seerat%20Ameer%20e%20Millat%20Pir%20syed%20jamat%20Ali%20shah.pdf

If Asrar really is sincere in his objectivity then we should see some sort of retraction from him on all these mistakes and false claims.

Bara’at al-Abrar ‘an Maka’id al-Ashrar by Mawlana Abdur Ra’uf Khan Jaganpuri Faizabadi written in the 1930s collecting the fatawa/statements and signatures of hundreds of nonpartisan scholars throughout the subcontinent opposing the takfir of Ahmad Rida Khan Barelwi:

https://ia601607.us.archive.org/13/items/BaraatUlAbraHighQuality/Baraat%20Ul%20Abrar%20High%20Quality.pdf

Alhamdulillah A beautiful article